サハラ砂漠の謎 ニジェールの失われた要塞集落

【ニジェールAFP=時事】西アフリカ・ニジェールの北東部にあるサハラ砂漠を進み続けると、サヘル地域(サハラ砂漠の南縁部)で最も見ごたえのある、息をのむような光景の一つが目に飛び込んでくる。塩と粘土でできた、要塞化された集落の遺跡だ。(写真は西アフリカ・ニジェールのジャドにある要塞〈資料写真〉)

【ニジェールAFP=時事】西アフリカ・ニジェールの北東部にあるサハラ砂漠を進み続けると、サヘル地域(サハラ砂漠の南縁部)で最も見ごたえのある、息をのむような光景の一つが目に飛び込んでくる。塩と粘土でできた、要塞化された集落の遺跡だ。(写真は西アフリカ・ニジェールのジャドにある要塞〈資料写真〉)ニジェールのファシには、こうした集落がいくつも点在している。集落は「クサール」と呼ばれているが、その詳細についてはほぼ分かっていない。

地域社会におけるファシの伝統的首長は「私たちが聞いているのは、トルコからやって来たアラブ人が、要塞を建設するというアイデアを当時の人々に伝えたということ。その結果、この要塞が築かれ、ここに存在している。頑丈で、これまでのところ持ちこたえている」と話した。建設された時期については「200年以上はたっていると推測できる」とした。

ファシの北にあるジャドには、岩の上に建つ壮大な要塞がある。地元住民らは、この要塞で観光客を呼び込めると期待を寄せる。

ただ、麻薬や武器の密売が盛んに行われている地域でもあるため、ここまでたどり着くのは、よほど覚悟を決めた人に限られる。

地元当局の関係者は、「今、本当に必要なのは観光だ。治安の悪さから、結果的にこの地域は要塞を(観光資源として)活用できていない」と話した。

地元の人々は、塩と粘土でできた遺跡が雨ざらしのままで適切に保護されていないと指摘する。また、ジャドの要塞をめぐっては、国連教育科学文化機関(ユネスコ)の世界遺産の暫定リストに記載されたまま、2006年以降は放置されているのが現状だ。

ユネスコの認定はファシの遺跡でも期待されている。ファシの伝統的首長は「(ファシの要塞を)ユネスコの世界遺産に登録することは必要であり、本当に重要なことだと常に言われている。要塞を通じて、私たちは団結する。要塞は私たちの文化と歴史の一部だ」と話した。

これらの遺跡をめぐっては、その謎を解明するための考古学的な発掘や科学的な調査は、これまで実施されたことはない。【翻訳編集AFPBBNews】

〔AFP=時事〕(2023/07/19-17:16)

Mystery of the desert-- The lost cities of the Nigerien Sahara

A long trek across the desert of northeastern Niger brings the visitor to one of the most astonishing and rewarding sights in the Sahel: fortified villages of salt and clay perched on rocks with the Saharan sands laying siege below.

Generations of travellers have stood before the ksars of Djado, wondering at their crenelated walls, watchtowers, secretive passages and wells, all of them testifying to a skilled but unknown hand.

Who chose to build this outpost in a scorched and desolate region -- and why they built it -- are questions that have never been fully answered. And just as beguiling is why it was abandoned.

No archaeological dig or scientific dating has ever been undertaken to explain the mysteries.

Djado lies in the Kawar oasis region 1,300 kilometres (800 miles) from the capital Niamey, near Niger's deeply troubled border with Libya.

Once a crossroads for caravans trading across the Sahara, Kawar today is a nexus for drug and arms trafficking.

Its grim reputation deters all but the most determined traveller.

There have been no foreign tourists since 2002, said Sidi Aba Laouel, the mayor of Chirfa, the commune where the Djado sites are located.

When tourism was good, there was economic potential for the community.

A blessing of sorts occurred in 2014, when gold was discovered. It saw an influx of miners from across West Africa, bringing life and some economic respite, but also bandits who hole up in the mountains.

Few of the newcomers seem interested to visit the ksars.

- Devastating raids -

The mayor is careful when speaking about local history, acknowledging the many gaps in knowledge.

He refers to old photocopies in his cupboard of a work by Albert le Rouvreur, a colonial-era French military officer stationed in Chirfa, who tried without success to shed light on the origins of the site.

The Sao, present in the region since antiquity, were the first known inhabitants in Kawar, and perhaps established the first fortifications.

But the timeline of their settlement is hazy. Some of the ksars still standing have palm roofs, suggesting they were built later.

Between the 13th and the 15th centuries, the Kanuri people established themselves in the area.

Their oasis civilisation was almost destroyed in the 18th and 19th centuries by successive waves of nomadic raiders -- the Tuaregs, Arabs and finally the Toubou.

The arrival of the first Europeans in the early 20th century spelt the beginning of the end of the ksars as a defence against invaders. The French military took the area in 1923.

Today, the Kanuri and Toubou have widely intermingled but the region's traditional leaders, called the mai, descend from the Kanuri lineage.

They act as authorities of tradition, as well as being custodians of oral history.

But even for these custodians, much remains a mystery.

Even our grandfathers didn't know. We didn't keep records, said Kiari Kelaoui Abari Chegou, a Kanuri leader.

- Threatened relics -

Three hundred kilometres to the south of Djado lies the Fachi oasis, famous for its fortress and old town, with the walls still almost intact.

Some symbolic sites of the ancient city are still used for traditional ceremonies.

A traditional authority of Fachi, Kiari Sidi Tchagam says the fortress is at least two hundred years old.

According to our information, there was an Arab who had come from Turkey, it was he who gave people the idea of making the fort there, he said, echoing theories of Turkish influence.

While the ruins are a point of pride, descendants are worried the fragile salt buildings, threatened by rain, are not properly safeguarded.

Since 2006, Djado has languished on a tentative list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

It's really crucial it's registered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, said Tchagam.

We are reminded of ourselves in this fort, it's a part of our culture, (it's) our entire history.

最新ニュース

-

加藤金融相「投資家は冷静に判断を」=株価急落に

-

ゆうちょ銀、一時システム障害=アプリなど利用できず

-

東京株、一時3万1000円割れ=1年半ぶり安値、世界株安止まらず

-

万博会場で基準値超メタンガス=大阪

-

相互関税の撤廃、米に要求

写真特集

-

ラリードライバー 篠塚建次郎

-

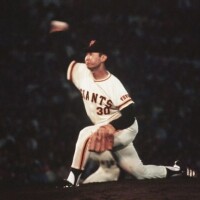

元祖“怪物” 巨人・江川卓投手

-

つば九郎 ヤクルトの球団マスコット

-

【野球】「サイ・ヤング賞右腕」トレバー・バウアー

-

【野球】イチローさん

-

【スノーボード男子】成田緑夢

-

【カーリング】藤沢五月

-

【高校通算140本塁打の強打者】佐々木麟太郎