戦禍の精神障害者施設、不安隠し平静装う キエフ

【AFP=時事】ウクライナの首都キエフ西郊ノボビルチの精神障害者施設で、看護師長のオクサナ・パダルカさんは、砲声で壁が揺れるたび物陰に隠れて涙をこぼす。それから無理に笑顔を作り、ウクライナは問題ないと患者を安心させる仕事に戻る。(写真は同施設の廊下にたたずむ患者)

【AFP=時事】ウクライナの首都キエフ西郊ノボビルチの精神障害者施設で、看護師長のオクサナ・パダルカさんは、砲声で壁が揺れるたび物陰に隠れて涙をこぼす。それから無理に笑顔を作り、ウクライナは問題ないと患者を安心させる仕事に戻る。(写真は同施設の廊下にたたずむ患者)「最初は、あまりの迫力にみんな座り込んでしまった。今はもう慣れた。ただ、ミサイルが飛んでこないことを祈るのみだ」とパダルカさん。

施設では18歳から80歳以上まで、男性患者355人が暮らす。わずか5キロの距離にあるイルピンとブチャは連日、ロシア軍の激しい攻撃を受けている。

120人いた施設スタッフは、2月24日のロシア軍侵攻後、半減した。看護師の1人はブチャ在住で、もう2週間も連絡が取れない。

患者や同僚に見られないよう自室にこもって、ひたすら泣くしかない夜もあると、パダルカさんは語る。患者たちの前で感情をあらわにはできない。「薬を飲めば、翌朝には元気になれる」

患者には常に笑顔で接する。「私たちが落ち着いているのを見て、患者さんは何も問題ない、大丈夫だと思える」

おびえる患者や、戦争はいつ終わるのかと聞いてくる患者もいる。「彼らを抱き締め、私たちは家族だと言う。すべてはうまくいっている、人生は素晴らしいんだと」

図書室では患者が黙々とチェスをしたり、塗り絵をしたり、粘土をこねたりしている。スタッフはできる限り日課をこなし、患者も可能な範囲で参加する。それでも、幾つか以前と変わったこともある。

図書室は、ウクライナ国旗の青色と黄色で彩られた。爆撃が激しくなったら、旧ソ連時代の地下壕(ごう)にすぐ逃げられるような服装で患者は寝ている。敷地内の散歩は制限され、インターネット利用も患者を不安にさせないため中止している。

テレビのチャンネルは、ウクライナの勝利を約束する公共放送に合わせている。「ウクライナは勝つ、当然だ」と、塗り絵にいそしむ40代の患者が言った。

別の患者が「ウクライナのために死ぬ覚悟はできている」と口にすると、医師が「いいや、ウクライナのために生きなければ」と穏やかに応じた。

戦争に関する冗談も時々飛び交う。昼食時、2個のゆで卵を手にした患者が「少なくとも、これはまだプーチンのものじゃない!」と叫んだ。

施設内には、重症患者用の隔離室もある。医師の一人は「もしプーチンがここに現れたら、その場で監禁してしまおう」と苦笑した。【翻訳編集AFPBBNews】

〔AFP=時事〕(2022/03/25-12:59)

Kyiv psychiatric home puts brave face on war

Sometimes, when war makes the walls of her Kyiv psychiatric hospital shudder, head nurse Oksana Padalka hides so she can cry.

Then she forces herself to smile and gets back to the job of reassuring her patients that everything is going well for Ukraine.

The first time, it was so powerful we all sat down. We're used to it now. We just hope we don't find ourselves in the path of some missile, she says.

War has descended on the north-western suburbs of Kyiv since Russian President Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine on February 24, his forces edging closer towards the capital.

Every day now, heavy artillery smashes into Irpin and Bucha, just a few kilometres (miles) away from the asylum in Novo-Bilytsky and its 355 residents.

It's been another night of shelling. Viktor Juravski, head of this neuropsychiatric home for men, is as exhausted as his colleagues.

The explosions were really very loud. And when the shooting starts, we just can't sleep at night, he says.

Half the pre-war 120 staff members have left. One of the nurses was from Bucha. Padalka hasn't had news of her for two weeks.

Some evenings I go to my room so my patients and colleagues can't see and just cry and cry, she says.

- 'We are their family' -

She can't show her emotions to the boys -- men whose families cannot care for them and who live, year-round, in the rectangular blocks of the hospital. The youngest is 18, the oldest over 80.

If I take a couple of pills, I'm fine the next morning, she admits.

Then she can put on some make-up and face the patients, all smiles.

If they see that we're calm, they think that everything is all right and that they'll be OK.

Some of the residents say they are frightened and others ask when the war is going to end.

We put our arms round them. We tell them we are their family. We show that we're there for them, that everything is fine. That life is good.

Today it's quiet and peaceful in the library, with its polished wooden floor, soft rugs and decorations -- paintings and pottery mostly, made by the patients.

About a dozen men aged between 35 and 60 are silently playing chess, colouring or making things with modelling clay.

The staff do everything they can to stick to their routine and patients pitch in when they can.

- Abba, Boney M. -

We still have electricity and food. Keeping to the daily routine reassures them, Juravski explains.

They also listen to music. Oleksyi loves everything by Abba. Sergei prefers Boney M.

There are some changes, though.

The library is dotted with blue and yellow, the colours of the national flag.

And tonight, patients will go to bed half dressed so they can rush down to the spartan Soviet-era bunker in the basement if the bombing gets too intense.

That has happened three or four times already. Everyone was back in bed within the hour, Juravski says.

Strolls in the grounds have been cut back and the patients no longer have internet access.

We don't want them to be upset by bad news or see something horrible, Padalka says.

The television, which some watch all day, is tuned to the Ukrainian public channel, a chirpy, somewhat grandiloquent mouthpiece of the resistance, promising victory against the Russian aggressor.

- 'Die for Ukraine' -

Ukraine's going to win. Of course, it is, says Yura. The 40-something is studiously colouring in a little deer with red and orange crayons.

We tell them what they want to hear -- that we're together, we're united and we're all in the same boat, head doctor Mikola Panassiuk explains.

We are ready to die for Ukraine, one of the patients calls out to him. The doctor replies gently, No, you should live for Ukraine.

Sometimes there are jokes about the war. Like when one of the residents takes two hardboiled eggs at lunchtime. At least these don't belong to Putin yet!

For the moment, the centre still has the essentials. But what if the power is cut off? Or the water? Or they find themselves trapped on the frontline?

Juravski winces. We don't even have a generator, he trails off.

Patients wander up and down the corridor or gaze, silently, out of the window.

Sometimes we have patients who are seriously ill, one doctor explains. Some are kept in padded cells, stripped of all potentially harmful objects.

Then he grins wryly: I tell you what, if Putin showed up here, we'd lock him away on the spot.

最新ニュース

-

加藤金融相「投資家は冷静に判断を」=株価急落に

-

ゆうちょ銀、一時システム障害=アプリなど利用できず

-

東京株、一時3万1000円割れ=1年半ぶり安値、世界株安止まらず

-

万博会場で基準値超メタンガス=大阪

-

相互関税の撤廃、米に要求

写真特集

-

ラリードライバー 篠塚建次郎

-

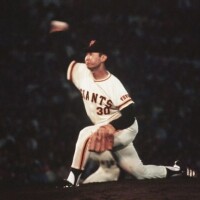

元祖“怪物” 巨人・江川卓投手

-

つば九郎 ヤクルトの球団マスコット

-

【野球】「サイ・ヤング賞右腕」トレバー・バウアー

-

【野球】イチローさん

-

【スノーボード男子】成田緑夢

-

【カーリング】藤沢五月

-

【高校通算140本塁打の強打者】佐々木麟太郎