ファッション業界に技術革新の波 藻類のコートに見る「緑の未来」

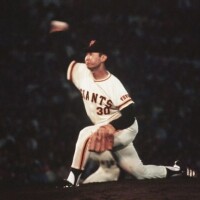

【パリAFP=時事】藻類から作られたドレスやバクテリア由来の染料、追跡可能な顔料の繊維への埋め込みなど、技術革新の波が訪れているファッション業界は今、環境への負荷をめぐるこれまでの悪評を払拭(ふっしょく)する絶好の機会を迎えている。(写真は藻類由来のレインコートを見せるデザイナーのシャーロット・マッカーディ氏。米ニューヨークで)

【パリAFP=時事】藻類から作られたドレスやバクテリア由来の染料、追跡可能な顔料の繊維への埋め込みなど、技術革新の波が訪れているファッション業界は今、環境への負荷をめぐるこれまでの悪評を払拭(ふっしょく)する絶好の機会を迎えている。(写真は藻類由来のレインコートを見せるデザイナーのシャーロット・マッカーディ氏。米ニューヨークで)ファッション業界の改革は急務だ。英エレン・マッカーサー財団によると、同業界が消費する水は年間約930億立方メートルに上り、海洋に流出される合成繊維片(マイクロファイバー)は約50万トン。また、炭素排出量では世界の約10%を占めるという。

変化を求める声が高まる中、独創的なアイデアが登場している。米ニューヨークのデザイナー、シャーロット・マッカーディ氏が手掛けた、藻類由来のレインコートもその一つだ。

藻類から作られた光沢のあるプラスチックは、印象的な(そしてカーボンフリーの)衣服に用いられる。

自らの仕事についてマッカーディ氏は、衣服の脱炭素化が可能であることを示す方法で、「これでもうけようとは思っていません。人々の心に種をまきたかっただけです」と語っている。

■バクテリア色

オランダでは、デザイナーのラウラ・ルヒトマン氏とイルファ・シーベンハー氏が、衣料の染色工程における有害な化学物質および水の大量消費の削減に取り組んでいる。

2人は、化学染色の代替手段を模索するプロジェクト「リビングカラー」を立ち上げ、そこで意外な協力者を見つけた──バクテリアだ。

一部の微生物には増殖しながら色素を放出するという特性がある。これを利用することで、衣服に鮮やかな色や柄を施すことができるのだ。

マッカーディ氏と同様に、2人も大量生産には興味がない。

以前はファストファッション業界で働いていたというルヒトマン氏は、「労働力の搾取や環境問題など、業界の負の側面を目の当たりにした」とし、事業を小規模にとどめたいとの考えを示している。

■企業のマスト

専門家の中には、このような取り組みが本格的な改革につながることに懐疑的な見方を示す人もいる。

英リーズ大学デザイン学科で持続可能性について教えるマーク・サムナー氏は、「いくつかの取り組みはこの業界で需要を見いだせるかもしれないが、新たなアプローチが越えなければならないハードルは高い」と指摘する。

サムナー氏は、既存のシステムを置き換えることよりも、改善することで最大の効果が期待できると考えている。「責任のあるブランドや小売業者らにとって持続可能性とは、もう一過性のブームではなく、ビジネスに必要不可欠なエレメントと考えられています」

■素材の追跡

透明性の確保を優先課題と見る向きは強い。

ファッション産業のあり方を問い直す国際活動団体「ファッション・レボルーション」のデルフィーヌ・ウィリオット氏は、サプライチェーンがあまりにも複雑化していることから、「多くの企業は自社の衣料がどこで作られているのか、生地がどこで生産されているのか、原材料の供給者が誰なのかを知りません」と指摘する。

こうした状況を改善すべく、新しいアイデアを提示したのは衣料のトレーサビリティー(追跡可能性)を手掛ける「ファイバートレース」だ。同社は、ファッション小売業の業界誌「ドレーパーズ」で、今年のサステナビリティ賞に選ばれた。

ファイバートレースの技術では、除去不可能な生物発光性の顔料を糸に付着させる。この糸が使われた衣料では、バーコードのスキャンと同じ要領で原産地などを知ることができるのだ。

ファイバートレースのアンドルー・オラー氏は、「衣服がどこで作られたかが分からなければ、環境への影響を知ることはできません」と語る。

また、「サプライチェーンを公開しないのは、何かを隠しているか、愚かであるかのどちらかです」としながら、「やらなければならないことは多いですが(中略)私はとても楽観しています」と続けた。【翻訳編集AFPBBNews】

〔AFP=時事〕(2021/06/21-10:57)

Fashion's green future of seaweed coats and mushroom shoes

From making algae-sequin dresses, dyeing clothes with bacteria to planting trackable pigments in cotton, an emerging tide of technological innovations offers the fashion industry a chance to clean up its woeful environmental record.

Change is urgently needed, since the industry consumes 93 billion cubic metres of water per year, dumps 500,000 tonnes of plastic microfibres into the ocean, and accounts for 10 percent of global carbon emissions, according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

The growing demands for change have generated ingenious responses, such as New York designer Charlotte McCurdy's seaweed raincoat.

The shimmering algae-plastic she concocted in a lab made for a striking (and carbon-free) garment, even more so when she teamed up with fashion designer Phillip Lim to make a sequin dress.

They are unlikely to show up in department stores. She sees them more as a way to demonstrate that decarbonised clothes are possible.

I'm not trying to monetise it. I just want to plant a seed, she told AFP.

Material development is so slow and it's so hard to compete with cellphone apps for funding. Frankly, I take climate change seriously and I don't have time, said McCurdy, whose focus now is on forming an innovation and outreach hub.

- Bacterial colours -

Others, like Dutch designers Laura Luchtman and Ilfa Siebenhaar of Living Colour, are finding ways to reduce the toxic chemicals and intensive water consumption of dyeing clothes.

They found an unlikely ally in bacteria.

Certain micro-organisms release natural pigments as they multiply, and by deploying them on fabric, they dye clothes in striking colours and patterns.

The research is published freely online and the pair have no interest in mass-production.

Luchtman, who previously worked in fast-fashion, saw up close the negative impact of that industry in terms of exploiting people and ecological problems and is determined to stay small-scale.

Others, however, hope such ideas can infiltrate big business.

Californian start-up Bolt Threads recently teamed with Adidas, Lululemon, Kering and Stella McCartney to build production facilities for Mylo, a leather made from mushroom roots.

McCartney displayed her first Mylo collection in March, and Adidas has promised a Mylo sneaker by the end of the year.

- Business imperative -

Some experts are sceptical that such initiatives can lead to large-scale transformation.

Maybe some of these things will get a foothold in the industry, but the bar is very high for new approaches, warns Mark Sumner, a sustainability expert at the University of Leeds School of Design.

It's an incredibly diverse industry with thousands of factories and operators all doing different things. It's not like the car industry where you only have to convince six or seven major companies to try something new.

Sumner sees the biggest impact coming from improving rather than replacing the existing systems and says pressure from consumers and NGOs means this is already happening.

Among responsible brands and retailers, this has genuinely moved away from being a fad. They are now considering sustainability as a business imperative, he told AFP.

Not that there are any right or wrong answers. The sustainability movement's strength comes from many actors pulling in the same direction.

Many different strategies need to run together, said Celine Semaan, founder of the Slow Factory Foundation which supports multiple social and environmental justice initiatives around fashion, including McCurdy's algae-sequin dress.

Technology won't resolve the issues on its own. It needs policy, culture, ethics, Semaan said.

- Cotton tracing -

One area many see as a priority, however, is transparency, and here technology has a clear role to play.

Such is the complexity of supply chains that many companies have no idea where their garments are made, where fabrics come from, who provides their raw materials, said Delphine Williot, policy coordinator for Fashion Revolution, a campaign group.

Recent uproar over reports that cotton from China's Xinjiang region was picked by forced labour was compounded by the difficulty of knowing where this cotton ended up. Beijing denies the allegations.

Fibretrace, which won a sustainability award from Drapers magazine this year, offers a possible solution.

It implants an indestructible bioluminescent pigment into threads. Any resulting garment can then be scanned like a barcode to find its origins.

You can't find the environmental impact of anything unless you know where it was made, Andrew Olah, Fibretrace's sales director, told AFP.

Combined with data sites like SourceMap and Open Apparel Registry that give companies unprecedented clarity on their supply chains, it has become increasingly hard to plead ignorance.

When you don't share your supply chain, you either do it because you're hiding something or you're stupid, said Olah.

There's a lot of work to do, he added. But I'm very optimistic.

最新ニュース

-

秋田市長に沼谷氏初当選=4期16年の現職破る

-

秋田知事に鈴木氏初当選=保守分裂、元副知事ら破る

-

東名や中央道などでETC障害=7都県の料金所、利用できず―レーン開放、事後精算呼び掛け

-

患者搬送のヘリ墜落=6人救助、1人死亡―長崎・対馬沖

-

秋田知事に鈴木氏初当選=保守分裂、元副知事ら破る

写真特集

-

ラリードライバー 篠塚建次郎

-

元祖“怪物” 巨人・江川卓投手

-

つば九郎 ヤクルトの球団マスコット

-

【野球】「サイ・ヤング賞右腕」トレバー・バウアー

-

【野球】イチローさん

-

【スノーボード男子】成田緑夢

-

【カーリング】藤沢五月

-

【高校通算140本塁打の強打者】佐々木麟太郎