弾圧強まるロシアで環境保護活動担う若者たち

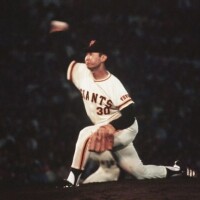

【ペンザ(ロシア)AFP=時事】ロシア西部ペンザ近郊で、環境活動家のエゴール・チャストヒンさん(18)は、悪臭を放つ生ぬるい汚水を放出する排水管にフラスコをあてがった。(写真は、同市近郊でごみ捨て場の検査に当たる環境活動家)

【ペンザ(ロシア)AFP=時事】ロシア西部ペンザ近郊で、環境活動家のエゴール・チャストヒンさん(18)は、悪臭を放つ生ぬるい汚水を放出する排水管にフラスコをあてがった。(写真は、同市近郊でごみ捨て場の検査に当たる環境活動家)他の10代の活動家アレクセイ・ゼトキンさんら2人が見守る中、チャストヒンさんは「ハーブティーのような香りがする」とジョークを飛ばし、妻のソニアさんは匂いや黄色っぽい色などの情報をメモに取った。

この汚水の源は、過去に汚染を理由に罰金を科されたことのある製紙工場だ。水は、ロシアの首都モスクワから約600キロ離れたスラ川の支流に流れていく。

チャストヒンさんらはその場で液体の分析テストを行い、高いレベルの塩素や鉄、有機物の存在を確認した。

「この水を飲んだり、魚を捕獲したり、水浴びしたりする人たちは危険性を認識しておくことが必要だ」と、チャストヒンさんはAFPに語った。だが、恐らく現実はそうならないだろう。

ロシア政府と関係を持たない、チャストヒンさんのような環境保護団体は、当局から圧力を受けてきた。ロシアがウクライナに侵攻して以降に始まった前例のない反体制運動弾圧により、こうした団体の前途には暗雲が垂れ込めている。

ロシア政府は国際環境NGOグリーンピースや世界自然保護基金(WWF)、数十の西側関連団体を「望ましくない」存在として活動を禁止した。

同国の環境NGOベローナで在外コーディネーターを務めるクセニア・バフルシェワ氏はAFPに対し、「体系的な変革」をもたらすような力を持ったロシアの環境団体はもはや存在しないと語った。

■「国家への脅威」

ロシアに残る環境保護活動は、資金や人材が不足する中、危険を承知で活動を続けるチャストヒンさんのような人々の双肩にかかっている。

「われわれがやっていることは合法であり、損害を与えるものではない。だがあすにも、過激主義やテロと関連付けられる可能性がある。少しの情報を伝えることも、国家への潜在的な脅威と見なされかねない」とチャストヒンさんは語った。

そこへ突然、当局の報道担当者とカメラを持った工場の従業員が現れた。こうした状況下では、警察が姿を見せることもある。チャストヒンさんらはその場を立ち去った。

■「小さな勝利」

チャストヒンさんらのグループは、川やごみ捨て場の検査を定期的に実施している。法律にたけた経験豊富な活動家と共に、違反事項を地元の検察官や環境保護機関に報告している。

時には意外な成功を収めることもある。2021年11月、当時高校生だったチャストヒンさんと友人のゼトキンさんは、その製紙工場の排水を検査した。

ゼトキンさんは検査結果を当局に送り、違反が確認されたため、当局は工場経営者に約5000ドル(約70万円)の罰金を科した。この工場は、与党の統一ロシアに所属する地元政治家が経営しており、後に装置を近代化するための投資を表明した。

ゼトキンさんは当時、政府寄りの環境団体のメンバーだったが、組織を監督する指導者の承認なしに検査を実施したとして告発され、組織から除名された。

ゼトキンさんは昨年2月、自ら「エコスタート」を設立し、チャストヒンさんと共に活動している。

チャストヒンさんは自らを「トロツキー主義的な国際主義者」と称し、「スターリン主義派」や政治的な弾圧に反対しているとの立場を示した。

ロシアの多くの若者が政治的に無関心かウラジーミル・プーチン大統領を支持する中、ゼトキンさんは、ウクライナ紛争により多くの人々が政治について考えるようになり、その一部は政府を支持したり、反対したりする立場を取るようになったと考えている。

ゼトキンさんは「今、政治に関わらなければ、あすには政治が向こうからやってくるだろう」と話した。【翻訳編集AFPBBNews】

〔AFP=時事〕(2023/09/13-17:15)

Russian teen eco-activists fight for future as risks mount

Egor Chastukhin, an 18-year-old environmental activist, holds a flask to a drain spurting out warm, putrid water near the historic city of Penza in western Russia.

It smells like herbal tea, he jokes after taking a waft of the sample while Sonia, his wife, jots down notes.

She records the odour and its yellowish colour as two other teenage activists, Alexei Zetkin and Yakov Demidov, look on.

The water's source is a nearby paper factory previously fined for pollution. Its destination is a tributary of the Sura river, around 600 kilometres (372 miles) from Russia's capital Moscow.

The group carries out a spot test on the liquid, which shows excess levels of chlorine, iron and organic matter.

People who drink this water, fish in it and bathe in it need to understand the danger, Egor told AFP.

The chances of that happening are slim.

Environmental groups in Russia not linked to the government -- those like Egor's -- have long faced pressure from authorities.

And since an unprecedented crackdown on dissent launched after Russia's military intervention in Ukraine, their future is in doubt.

Russia has outlawed the work of Greenpeace and the World Wide Fund for Nature, branding them and dozens of other Western-linked groups undesirable.

The exiled coordinator of the climate action nonprofit Bellona, Ksenia Vakhrusheva, told AFP there were no longer any Russian environmental organisations powerful enough to bring about systemic change.

- 'Threat to the state' -

What remains of ecological advocacy in Russia rests on the shoulders of under-resourced activists like Egor, who are still trying to raise awareness in spite of the risks.

What we're doing is legal and harmless. But tomorrow they could link it to extremism or terrorism. The slightest transmission of information could become an alleged threat to the state, Egor says.

Suddenly, a press officer and factory employee holding a camera arrive on the scene, with the rag-tag group taking off after a security guard appears -- a move that is sometimes followed by a police visit.

Several metres away, men under some trees continue to fish the polluted water.

The group regularly inspects rivers and dumps. Together with a more experienced activist with a legal background, they report violations to local prosecutors or the environmental protection agency.

Sometimes with surprising success.

In November 2021, Egor and his friend Alexei, then high school students, tested the water discharged by the paper factory.

- Small victories -

Alexei sent the results to the authorities, who fined the factory manager about $5,000 after confirming the violations.

The factory is run by a local politician from the Kremlin-loyal United Russia party, and says it has since invested in modernising its equipment.

Following the probe, Alexei, then a member of a pro-government environmental group, was accused of carrying out the inspection without the approval of his superiors and kicked out.

In February last year, he set up Eko-Start, and he and Egor campaign together.

After the factory, activists and AFP journalists visited a landfill outside Penza, a jumble of rotting vegetables, batteries and medical waste emitting toxic fumes.

The owners of the dump are high-ups in the region. They save money by not sorting the waste and not respecting the rules on storage, Alexei said.

Alexei met Egor in the Komsomol, the youth wing of the Russian Communist Party, which, though subservient to the Kremlin at the national level, sometimes represents opposition locally.

Both have since left the group.

Egor describes himself as a Trotskyite-internationalist, saying he is against Stalinists and political repression.

While many young Russians are apolitical or support President Vladimir Putin, Alexei thinks the conflict in Ukraine has politicised many, and pushed some to take a stand in opposing -- or supporting -- the government.

If you don't do politics today, politics will come for you tomorrow, he says.

最新ニュース

-

秋田市長に沼谷氏初当選=4期16年の現職破る

-

秋田知事に鈴木氏初当選=保守分裂、元副知事ら破る

-

東名や中央道などでETC障害=7都県の料金所、利用できず―レーン開放、事後精算呼び掛け

-

患者搬送のヘリ墜落=6人救助、1人死亡―長崎・対馬沖

-

秋田知事に鈴木氏初当選=保守分裂、元副知事ら破る

写真特集

-

ラリードライバー 篠塚建次郎

-

元祖“怪物” 巨人・江川卓投手

-

つば九郎 ヤクルトの球団マスコット

-

【野球】「サイ・ヤング賞右腕」トレバー・バウアー

-

【野球】イチローさん

-

【スノーボード男子】成田緑夢

-

【カーリング】藤沢五月

-

【高校通算140本塁打の強打者】佐々木麟太郎