ヤン・ヨンヒ監督の描く在日コリアン家族の肖像 最新作公開へ

【ソウルAFP=時事】数々の受賞歴を持つ在日コリアンの映画監督ヤン・ヨンヒ氏(57)が北朝鮮へ渡る長兄を見送ったのは、まだ6歳の時だった。長兄は、北朝鮮の当時の最高指導者、金日成(キム・イルソン)氏の還暦祝いの「贈り物」として選ばれ、北に送られた200人のうちの一人だった。(写真は映画監督のヤン・ヨンヒ氏。韓国ソウルで行ったAFPのインタビューで)

【ソウルAFP=時事】数々の受賞歴を持つ在日コリアンの映画監督ヤン・ヨンヒ氏(57)が北朝鮮へ渡る長兄を見送ったのは、まだ6歳の時だった。長兄は、北朝鮮の当時の最高指導者、金日成(キム・イルソン)氏の還暦祝いの「贈り物」として選ばれ、北に送られた200人のうちの一人だった。(写真は映画監督のヤン・ヨンヒ氏。韓国ソウルで行ったAFPのインタビューで)北朝鮮の賛歌が流れ、紙吹雪が舞う中、船が新潟港を出る前に兄からメモを手渡された。「ヨンヒ、音楽をいっぱい聴くように。映画も好きなだけ見るように」と書いてあった。1972年のことだ。

すでにその1年前、両親は2番目と3番目の兄も北朝鮮へ送り出していた。金政権が、すべての人に雇用と無償の教育・医療を提供するという社会主義の「楽園」を約束していたためだ。

兄たちは北朝鮮へ行ったままとなった。

「あんな無意味な事業を思いつき、自分の子どもを差し出させた体制に、私の両親は人生のすべてをささげたのです」とヤン氏はAFPに語った。

大阪生まれのヤン氏の作品には、どれも兄たちと引き離された心の痛みが映し出されている。朝鮮半島が日本の植民地支配を脱した頃から、南北に分断されて数十年たった後まで、世代をまたいだ家族の苦悩が記録されている。

日本と北朝鮮の政府は、1959年から1984年にかけて在日朝鮮人の帰還事業を進めた。この事業を通じて、約9万3000人が北朝鮮へ渡った。

北朝鮮系の団体、在日本朝鮮人総連合会(朝鮮総連)の大阪の幹部だったヤン氏の父親は、1970年代に3人の息子を送った。

だが、金政権は帰還事業に関する約束をほとんど果たさず、家族は北へ送った身内を呼び戻すこともできなかった。

「子どもを送った両親に選択の余地はありませんでした。息子たちの安全を守るために、体制から離れることができず、いっそう忠誠を尽くすしかありませんでした」とヤン氏。「兄たちを人質に取る体制に、非常に怒りを覚えました」

■「自由になりたかった」

ヤン氏は日本で差別に直面したと言う。仕事では何度も不採用になり、朝鮮人だからと映画プロジェクトから外されたこともあった。

同時に、在日朝鮮人コミュニティーの中の親北感情にも反抗した。

朝鮮総連が運営する大学で文学を学んでいた時、北朝鮮2代目の最高指導者、金正日(キム・ジョンイル)氏の「文学理論」に沿ったテキストの解釈が学生に求められた。ヤン氏は一度、白紙のまま提出したことがあると語った。

「私は自由になりたかったのです」とヤン氏は言う。「日本人のふりをして、父や兄たちのことをごまかすこともできました。何も問題を意識していないかのように振る舞って」

「でも本当に自由になるには、すべてと向き合う必要がありました」

結婚に失敗し、3年ほど北朝鮮系の高等学校で教師をした後、ドキュメンタリー映画の製作を学ぶためにニューヨークへ向かった。そして、映画を通じて家族のストーリーを語り始めた。

2005年に公開された最初のドキュメンタリー映画『ディア・ピョンヤン』は、米サンダンス映画祭やベルリン国際映画祭で批評家に絶賛された。

北朝鮮を内側から独自の視点で描いた貴重な作品で、ヤン氏が兄たちと会うため北朝鮮を訪れるたびにビデオカメラで撮影した映像が使用されている。

朝鮮総連はこのドキュメンタリーに激怒し、謝罪を求めた。その頃にはヤン氏はすでに韓国籍を取得しており、兄たちに再び会うために北朝鮮へ行くことはできなくなっていた。

「とてつもない代償でしたが、後悔していません。少なくとも、自分自身の願いを貫きました。映画を作ること、自分の家族の物語を語ることです」

■祖国が欲しい

模索の旅を続けるヤン監督の最新作が、今年劇場公開される予定の映画『スープとイデオロギー』だ。

この作品の主役は、自分の子どもをこよなく愛しながら、北朝鮮に深く忠誠を誓っているヤン氏の母、カン・ジョンヒさんだ。

母は45年もの間、平壌にいる息子たちに食料や金銭、その他の物資を送り続けた。現金と交換できるよう、セイコー製の腕時計を送ったこともある。

母はしばしば「不自然なほど、大げさに明るく」、息子たちは「首領様のおかげで」平壌で元気にしていると人に話していたとヤン氏は言う。

だが、特に一番上の兄が双極性障害(そううつ病)と診断された後は、「家では一人で泣いていたのでしょう」。母は何が必要かも分からないまま、治療薬を買えるだけ買って日本から送っていたという。その兄は2009年に亡くなった。

年老いてから母は、心に傷を負ったもう一つの出来事をヤン氏に語った。1947年から54年にかけて、韓国の済州島で島民の蜂起を鎮圧するために韓国軍が行った虐殺だ。韓国国家記録院によると、その間に3万人が殺害された。

ヤン監督の母は大阪生まれだったが、その頃、両親の故郷の済州島にいた。死者には親戚や婚約者も含まれていた。

「母は、祖国を心底欲しがっていた人です。済州島の住民になりたかったのに、離れざるを得ませんでした。日本には自分の居場所がないと思っていました」とヤン氏は語る。

「母は信じることのできる政府を求めていました。そして北朝鮮を信じたのです」。ヤン氏の2人の兄が今も暮らす国だ。

さまざまな困難に直面しながらも、ヤン氏は声を上げたかったと言う。「若い時からいつも、『これを言うな、あれを言うな、いつもこう言え』と言われていました」

「そして気付きました。どんな犠牲を払っても、私は声を上げたかったのだと」【翻訳編集AFPBBNews】

〔AFP=時事〕(2022/02/01-11:22)

Korean director takes on decades of generational trauma

Award-winning filmmaker Yang Yonghi was just six years old when she watched her eldest brother leave Japan for North Korea as one of 200 human gifts for leader Kim Il Sung's 60th birthday.

As a North Korean anthem blared, through bursts of confetti, he handed her a note before his ferry departed Niigata port: Yonghi, listen to a lot of music. Watch as many movies as you want.

It was 1972, a year after her parents -- members of the ethnic Korean Zainichi community in Japan -- had sent their other two sons the same way, lured by the Kim regime's promise of a socialist paradise with free education, healthcare and jobs for all.

The boys never moved back.

My parents dedicated their entire lives to an entity that came up with such a senseless project and forced them to sacrifice their own children for it, Yang, now 57, told AFP.

The trauma of being ripped apart from her siblings reverberates in all of Osaka-born Yang's films, which document the suffering of her family across generations -- from the end of Japanese colonial rule to decades after the split of the Korean peninsula.

Her father was a prominent pro-North Korean activist in Osaka, and had sent his sons to live there in the 1970s as part of a repatriation programme organised by Pyongyang and Tokyo.

Around 93,000 Japan-based Koreans left for North Korea under the scheme between 1959 and 1984. Yang's eldest brother was among 200 university students specially chosen to honour Kim Il Sung.

The regime's promises came to almost nothing, but the Zainichi arrivals were forced to stay. Their families could do little to bring them back.

Yang's parents had no choice after having already sent their children. To keep the kids safe (in North Korea), they couldn't leave the regime, and had to become even more devoted, she said.

I was so angry at the system that kept my brothers as hostages.

Unlike her parents, Yang rebelled.

- 'I wanted to be free' -

Yang said she faced discrimination in Japan -- repeatedly denied jobs and fired from a film project because of her Korean heritage.

She also had to grapple with the pro-North Korean sentiment in her community.

Her father was a prominent figure in the Chongryon organisation -- Pyongyang's de facto embassy in Japan -- which ran the university where she studied literature.

During her time at the school, when students were asked to interpret texts with leader Kim Jong Il's literary theories, Yang said she once submitted a blank page.

And at home, where portraits of North Korean leaders Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il hung side by side, she resented her parents for sending her brothers away.

I wanted to be free, Yang told AFP.

I could have... pretended I was Japanese, and avoided being honest about my father and brothers, acting as if I don't recognise any problems.

But to really break free, I had to confront them all.

After a failed marriage and spending some three years as a teacher at a Pyongyang-linked high school, she left for New York to study documentary filmmaking.

And it was through movies that she began to unpack the story of her family.

Her first documentary, Dear Pyongyang, was released in 2005 to critical acclaim, including at the Sundance and Berlin film festivals.

It offered a rare, independent look inside North Korea, featuring footage from Yang's camcorder during her trips to visit her brothers.

It infuriated the Chongryon, which demanded an apology.

By then, Yang had acquired South Korean nationality, making it impossible for her to ever visit her brothers again.

It's a huge price, but I have no regrets. I at least stayed true to my own desire -- to make a movie, and to tell a story about my own family, Yang explained.

- Desperate for a homeland -

Yang's latest step in that quest is the film Soup and Ideology, set for a theatrical release this year.

It focuses on her mother Kang Jung-hee, who fiercely loves her children but is also deeply loyal to Pyongyang.

For 45 years, she sent food, money and other goods to her sons in Pyongyang, including Seiko watches to be exchanged for cash.

Yang said her mother was often unnaturally and overly cheerful, telling people that her sons are doing well in Pyongyang thanks to the North Korean leaders.

But at home, she would cry alone, the director said, especially after Kang's eldest son was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

Yang said her mother would send any medicine for the disease she could afford from Japan to North Korea, without knowing what he might need.

He died in 2009.

In her old age, she told Yang of yet another traumatic event -- a bloody crackdown by South Korean forces on Jeju Island in 1947-54 to crush an uprising.

As many as 30,000 people were killed, according to the National Archives of Korea.

They included Kang's fiancee and relatives.

My mother is someone who desperately wanted a homeland. She wanted to belong to Jeju but she was forced to leave. She didn't see her place in Japan, Yang said.

She was looking for a government that she could trust, and she believed in North Korea.

That is where Yang's two surviving brothers remain.

Despite the struggles facing her, Yang said she still wanted to speak out.

Since I was young, I was constantly told: 'don't say this, don't say that, always say this', she told AFP.

I realised I wanted to do it whatever the price.

最新ニュース

-

中国の台湾演習に「深い懸念」=G7外相声明、対話促す

-

ルペン氏、大統領選「諦めない」=出馬禁止で抗議集会―仏

-

ETC障害、復旧作業続く=中日本高速

-

秋田市長に沼谷氏初当選=4期16年の現職破る

-

秋田知事に鈴木氏初当選=保守分裂、元副知事ら破る

写真特集

-

ラリードライバー 篠塚建次郎

-

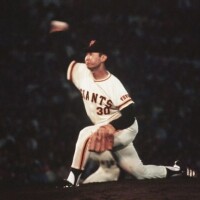

元祖“怪物” 巨人・江川卓投手

-

つば九郎 ヤクルトの球団マスコット

-

【野球】「サイ・ヤング賞右腕」トレバー・バウアー

-

【野球】イチローさん

-

【スノーボード男子】成田緑夢

-

【カーリング】藤沢五月

-

【高校通算140本塁打の強打者】佐々木麟太郎