ブルース・リー映画で武術独習 空手で五輪目指す難民アスリート

【シドニーAFP=時事】アシフ・スルタニさん(25)は、7歳の頃から五輪出場を目指してきた。アフガニスタンでの迫害に耐え、難民としてオーストラリアにたどり着くまでの道のりは苦しいものだった。しかし、空手の黒帯を持つスルタニさんが東京五輪への出場権を手にするまで、ついにあと一突きのところまで来た。(写真はアフガニスタン出身で難民の空手選手、アシフ・スルタニさん。豪シドニー郊外で)

【シドニーAFP=時事】アシフ・スルタニさん(25)は、7歳の頃から五輪出場を目指してきた。アフガニスタンでの迫害に耐え、難民としてオーストラリアにたどり着くまでの道のりは苦しいものだった。しかし、空手の黒帯を持つスルタニさんが東京五輪への出場権を手にするまで、ついにあと一突きのところまで来た。(写真はアフガニスタン出身で難民の空手選手、アシフ・スルタニさん。豪シドニー郊外で)スルタニさんは、難民アスリートとして奨学金を得ている56人の一人だ。現在、東京五輪の難民選手団入りを目指している。難民選手団は、2016年のリオデジャネイロ五輪で初めて結成された。

オーストラリアに渡るまでの9年間の旅は、内戦と少数民族ハザラ人への迫害から逃れるために家族でアフガニスタンを脱出した時に始まった。

イランまでの道のりは悪夢のように「恐ろしかった」と振り返る。家族は銃で武装した男たちに所持品を奪われ、誘拐されるか殺されるかの危険と常に隣り合わせだった。

イランでは穏やかな暮らしを送れるはずだと思っていたが、希望を抱いたのもつかの間のことだった。唾を吐き掛けられ、殴られ、執拗(しつよう)ないじめに遭ったスルタニさんは、護身術として武術を習い始める。

だが、不法入国者だったことから練習場を追い出され、指導者もいなかった。そこで裏庭に道場を手作りし、アクション映画スター、ブルース・リーのカンフー映画を繰り返し見ながら、見事な動きを手本に友人たちと練習を積んだ。

ところが、16歳の時、一人でアフガニスタンに強制送還されてしまう。

家族とは離れ離れになり、内戦も続いていた。スルタニさんは再びアフガニスタンを逃れ、インドネシアを経て、ぼろぼろの船でオーストラリアを目指した。

危うく命を落としかけながらたどり着いたオーストラリアでは、移民収容施設で数か月を過ごした。練習に打ち込むスルタニさんの様子を目にした施設の職員らも応援してくれるようになった。

難民認定を受けて、シドニー北部のメートランドに定住し、やっと新しい生活に踏み出した。

初めて教育を受けることができたのは18歳になってから。学校に行き、道場も見つけた。

以来、ますます空手の練習に力を入れている。スルタニさんにとって空手は、生きるか死ぬかの困難を克服する原動力となってきた。

「武術とは尊敬であり、規律であり、栄誉であり、忠義であり、立ち直る力である」とスルタニさん。空手は「人生で大きな部分を占めている。子どもだった私を救ってくれた」と続けた。【翻訳編集AFPBBNews】

〔AFP=時事〕(2021/06/08-13:46)

Bruce Lee, life of hardship inspire refugee's Tokyo Olympics dream

Asif Sultani has been fighting his way to the Olympics since he was seven years old, enduring persecution in Afghanistan and a grim journey to refuge in Australia.

But the karate black belt is now within punching distance of a spot at the Tokyo Games.

At 25, Sultani says he has seen some of the darkest parts of humankind.

As he vies for a spot on the Refugee Olympic Team, he is spurred on by memories of his harrowing journey to Australia, on a rickety boat where he nearly lost his life.

When the vessel broke down in the dark somewhere off Indonesia, panic gripped the more than 100 asylum seekers crammed onboard.

Others fought over the small number of life jackets, but Sultani never tried to find one for himself -- he could not shift his gaze from a child playing as waves threatened to sink the boat.

(The child) didn't have any idea we were about to drown; it just reminded me of my own childhood, he told AFP in a dojo in Sydney's west.

Although the boat eventually kicked back to life and delivered Sultani to Australia, the child's vulnerability shook him deeply, fuelling his Olympic ambition of representing the tens of millions of forcibly displaced children around the world.

I have millions of reasons to compete at the Games, he said.

He is now one of the 56 refugee athlete scholarship-holders competing for a place on the Refugee Olympic Team, which made its debut at the 2016 Rio Games. The team will be announced on June 8.

That inspired me, seeing that first Refugee Olympic Team in Rio, and I said, 'Finally, I can be part of that team, that not only represents myself but millions of other people around the world.'

- Spat at, beaten -

Sultani's nine-year journey to Australia started when his family fled Afghanistan because of war and the persecution of their Hazara community.

On a horrifying trip to Iran, which Sultani compares to a nightmare, they were robbed by gunmen and terrified of being kidnapped or killed at any moment.

But any hope of a peaceful life in Iran was short-lived.

Spat at, beaten and bullied relentlessly, Sultani turned to martial arts to defend himself, training at an Iranian studio.

But as an undocumented refugee, he was kicked out of the gym within months.

I was heartbroken, and it was really, really hard for me because that's the only thing that I had, he said.

Without a gym or a trainer, he turned his backyard into a makeshift dojo and used classic Bruce Lee kung fu films for guidance -- watching them repeatedly, and practising his best moves with friends.

He inspired me as a kid, you know, to never give up on my dream, Sultani said.

But at 16, he was deported alone, back to Afghanistan.

Without his family and with conflict still raging, Sultani fled Afghanistan again, reaching Indonesia before boarding the boat to Australia.

- 'Born a refugee' -

After his dangerous voyage, he would spend months in Australian immigration detention, where his commitment to training brought him support from the guards.

One officer would arrive early in the morning to run with Sultani, and others would encourage him too. The difference from his early life was stark.

When we're born, we don't have a choice -- we're just born a refugee, he said.

People's support means everything to us because we've lost everything... I'm really grateful to this day to those officers that they actually encouraged me.

After gaining refugee status, he settled in Maitland, north of Sydney, and began shaping his new life.

Aged 18, it was the first time he could get an education, so he enrolled in school and found a dojo.

With little money and no car, he would wake at 5am every morning and run to the dojo and back -- clocking up 20 kilometres (12 miles) a day -- before heading to school.

Since then, his commitment to the sport has only grown, and he credits karate with giving him the drive to overcome his life-threatening obstacles.

Martial arts is about respect; it's about discipline, about honour, loyalty, and resilience, he said.

It has been a big part of my life, and it did save my life as a child.

As he waits to hear if he has made the team for Tokyo, he eyes a goal beyond gold -- to give refugee children a role model they can relate to.

That regardless of who they are or where they come from, they have the ability to achieve greatness.

最新ニュース

-

円相場、146円62~63銭=7日正午現在

-

戦艦大和、戦没者を追悼=撃沈80年、遺族ら参列―広島・呉

-

ゆうちょ銀行でシステム障害=アプリやネットバンキング利用できず

-

旧統一教会が即時抗告=東京地裁の解散命令に不服

-

アジア株も軒並み急落

写真特集

-

ラリードライバー 篠塚建次郎

-

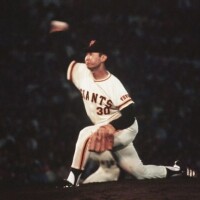

元祖“怪物” 巨人・江川卓投手

-

つば九郎 ヤクルトの球団マスコット

-

【野球】「サイ・ヤング賞右腕」トレバー・バウアー

-

【野球】イチローさん

-

【スノーボード男子】成田緑夢

-

【カーリング】藤沢五月

-

【高校通算140本塁打の強打者】佐々木麟太郎