2022.06.17 13:00World eye

黒死病の起源特定 600年以上の謎、DNA分析で解明

【AFP=時事】14世紀に流行した黒死病(ペスト)の起源をキルギスの一地域に特定したとする研究論文が15日、英科学誌ネイチャーに掲載された。(写真はキルギス北部の湖イシク・クル近くに1338年か39年に埋葬された人の墓碑。「疫病で死亡」と書かれている)

【AFP=時事】14世紀に流行した黒死病(ペスト)の起源をキルギスの一地域に特定したとする研究論文が15日、英科学誌ネイチャーに掲載された。(写真はキルギス北部の湖イシク・クル近くに1338年か39年に埋葬された人の墓碑。「疫病で死亡」と書かれている)黒死病は、500年近く続いたペストの世界的流行の第1波につけられた名称で、1346~53年のわずか8年間で欧州と中東、アフリカの人口の最大6割が犠牲になったと推定されている。発生源ははっきりせず、数世紀にわたり議論が続いていた。

論文を発表した研究チームの一員で、英スターリング大学の歴史学者であるフィリップ・スラビン准教授は、現在のキルギス北部にある14世紀の墓地について書かれた1890年の論文に手がかりを発見した。論文によると、同地域では黒死病流行の7~8年前に当たる1338~39年に埋葬が急増。複数の墓碑には「疫病で死亡」と記されていた。

スラビン氏は埋葬された人々の死因を探るべく、古代のDNA分析を専門とする研究者と協力。AFPの取材に応じた論文の筆頭著者、独テュービンゲン大学のマリア・スピロウ氏によると、埋葬されていた7人の歯からDNAを採取し、数千種類の微生物遺伝子と比較したところ、ペスト菌であることが判明した。

スピロウ氏は、歯の中には多くの血管があり「死因となったと考えられる血液感染性の病原菌が検出される可能性が高い」とAFPに説明した。

黒死病の流行は、げっ歯類に寄生するノミにより運ばれるペスト菌が突然多くの系統に分岐した「ビッグバン」と呼ばれる現象により始まったとされる。この現象は早くて10世紀にも起きていたとみられていたが、具体的な時期ははっきりしていなかった。

研究チームは、採取したサンプルからペスト菌の遺伝子を解析し、菌の系統が分岐前のものであったことを特定。周辺地域に現在生息するげっ歯類からも同じ系統の菌が見つかったことから、「ビッグバン」がこの地域で黒死病流行の直前に起きたと結論付けた。【翻訳編集AFPBBNews】

〔AFP=時事〕(2022/06/17-13:00)

2022.06.17 13:00World eye

Black Death origin mystery solved... 675 years later

A deadly pandemic with mysterious origins: it might sound like a modern headline, but scientists have spent centuries debating the source of the Black Death that devastated the medieval world.

Not anymore, according to researchers who say they have pinpointed the source of the plague to a region of Kyrgyzstan, after analysing DNA from remains at an ancient burial site.

We managed to actually put to rest all those centuries-old controversies about the origins of the Black Death, said Philip Slavin, a historian and part of the team whose work was published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

The Black Death was the initial wave of a nearly 500-year pandemic. In just eight years, from 1346 to 1353, it killed up to 60 percent of the population of Europe, the Middle East and Africa, according to estimates.

Slavin, an associate professor at the University of Stirling in Scotland who has always been fascinated with the Black Death, found an intriguing clue in an 1890 work describing an ancient burial site in what is now northern Kyrgyzstan.

It reported a spike in burials in 1338-39 and that several tombstones described people having died of pestilence.

When you have one or two years with excess mortality it means that something funny was going on there, Slavin told reporters.

But it wasn't just any year -- 1338 and 1339 was just seven or eight years before the Black Death.

It was a lead, but nothing more without determining what killed the people at the site.

For that, Slavin teamed up with specialists who examine ancient DNA.

They extracted DNA from the teeth of seven people buried at the site, explained Maria Spyrou, a researcher at the University of Tuebingen and author of the study.

Because teeth contain many blood vessels, they give researchers high chances of detecting blood-borne pathogens that may have caused the deaths of the individuals, Spyrou told AFP.

- 'Big Bang' event -

Once extracted and sequenced, the DNA was compared against a database of thousands of microbial genomes.

One of the hits that we were able to get... was a hit for Yersinia pestis, more commonly known as plague, said Spyrou.

The DNA also displayed characteristic damage patterns, she added, showing that what we were dealing with was an infection that the ancient individual carried at the time of their death.

The start of the Black Death has been linked to a so-called Big Bang event, when existing strains of the plague, which is carried by fleas on rodents, suddenly diversified.

Scientists thought it might have happened as early as the 10th century but had not been able to pinpoint a date.

The research team painstakingly reconstructed the Y. pestis genome from their samples and found the strain at the burial site pre-dated the diversification.

And rodents living in the region now were also found to be carrying the same ancient strain, helping the team conclude the Big Bang must have happened somewhere in the area in a short window before the Black Death.

The research has some unavoidable limitations, including a small sample size, according to Michael Knapp, an associate professor at New Zealand's University of Otago who was not involved in the study.

Data from far more individuals, times and regions... would really help clarify what the data presented here really means, said Knapp.

But he acknowledged it could be difficult to find additional samples, and praised the research as nonetheless really valuable.

Sally Wasef, a paleogeneticist at Queensland University of Technology, said the work offered hope for untangling other ancient scientific mysteries.

The study has shown how robust microbial ancient DNA recovery could help reveal evidence to solve long-lasting debates, she told AFP.

最新ニュース

写真特集

-

ラリードライバー 篠塚建次郎

-

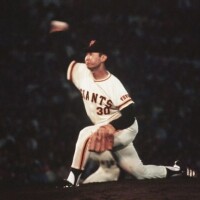

元祖“怪物” 巨人・江川卓投手

-

つば九郎 ヤクルトの球団マスコット

-

【野球】「サイ・ヤング賞右腕」トレバー・バウアー

-

【野球】イチローさん

-

【スノーボード男子】成田緑夢

-

【カーリング】藤沢五月

-

【高校通算140本塁打の強打者】佐々木麟太郎