八方ふさがりのロヒンギャ難民 弾圧による大量避難から5年

【クトゥパロンAFP=時事】バングラデシュにあるロヒンギャ難民キャンプの学校で、モハマド・ユスフさん(15)は毎朝、ミャンマー国歌を歌っている。(写真はバングラデシュ・ウキヤのクトゥパロン難民キャンプの学校で学ぶロヒンギャの子ども)

【クトゥパロンAFP=時事】バングラデシュにあるロヒンギャ難民キャンプの学校で、モハマド・ユスフさん(15)は毎朝、ミャンマー国歌を歌っている。(写真はバングラデシュ・ウキヤのクトゥパロン難民キャンプの学校で学ぶロヒンギャの子ども)仏教徒が多数を占めるミャンマーで国軍が少数派イスラム教徒ロヒンギャを迫害し、大規模な難民流出が始まってから8月25日で5年を迎えた。少なくとも数千人が軍に殺害されたとみられ、ユスフさん一家をはじめ、74万人以上がバングラデシュに逃れた。

不衛生なキャンプで暮らすユスフさんら大多数のロヒンギャの子どもは、教育を受ける機会をほとんど与えられてこなかった。子どもたちに教育を受けさせれば、帰還がすぐには実現しそうにないと認めることになりかねないとバングラデシュ政府が懸念したためだ。

昨年のミャンマーの軍事クーデターによって、ロヒンギャ帰還の見通しはいっそう遠のいたとみられており、バングラデシュ政府は今年7月にようやく、国連児童基金(ユニセフ)に対し、ロヒンギャの子ども13万人に教育を受けさせる計画を許可した。いずれは難民キャンプにいる子ども全員に教育の機会が提供される見込みだ。

だが、バングラデシュ政府は今なお、ロヒンギャ難民の帰還を望んでいる。そのため授業はミャンマーのカリキュラムに沿ってビルマ語で行われ、さらに毎日始業の際にミャンマーの国歌を子どもたちに歌わせている。

オランダ・ハーグの国際司法裁判所(ICJ)では、ミャンマー国軍のロヒンギャへの弾圧がジェノサイド(集団殺害)に当たるかどうかを審理する裁判が行われている。だが、ユスフさんはミャンマー国歌を大事にしていると言う。

「ミャンマーは私の祖国です」とユスフさん。「この国にひどい目に遭わされたわけじゃない。ひどいことをしたのは、権力を持った人たちです」

妹はミャンマーで亡くなり、同胞は虐殺されたと話す。「それでも、自分の国なのです」と続けた。

夢は航空関係のエンジニアかパイロットになることだ。「いつか世界中を飛び回りたい」と話した。

■「時限爆弾」

キャンプでは計100万人近いロヒンギャ難民が暮らしており、約半数は18歳未満だ。

バングラデシュ軍の元将軍マフズル・ラフマン氏は、同国政府が長期的な計画の必要性に「気付いた」のは、教育を受けていない若者がキャンプにいるリスクに着目したためだと指摘する。

キャンプの中では薬物を密売するギャングがうろつき、治安はすでに深刻な問題になっている。この5年間に起きた殺人事件は100件以上。武装勢力や犯罪集団は、キャンプ生活にうんざりしている若者の勧誘にも力を入れている。

ラフマン氏は、すべての子どもが「時限爆弾になりかねない」とAFPに語る。「教育も受けられず、夢も希望もないキャンプで育つと、どんな怪物になってしまうのか見当もつかない」

■ミャンマーにとどまったロヒンギャの苦難

一方、5年前にバングラデシュに逃れる道を選ばなかった人もいる。母親からミャンマーにとどまるよう懇願されたマウンソウナインさん(仮名)もその一人だ。

故郷と呼ぶ場所に今も住んでいるが、将来の計画を立てることはすっかり諦めたと話す。また弾圧で破壊されるかもしれないからと、雨期ごとの家の修理はやめてしまったため、自宅は荒れるがままになっている。

ミャンマーに残る約60万人のロヒンギャは、キャンプに収容されているか、あるいは村にとどまっている場合もミャンマー軍や国境警備隊に翻弄(ほんろう)され、いつまた生活が一変するか分からない。

大半は市民権を与えられず、移動や医療、教育に関して制限を受けている。国際人権団体ヒューマン・ライツ・ウオッチはロヒンギャに対するこうした処遇を、かつての南アフリカのアパルトヘイト(人種隔離政策)になぞらえて非難している。

ロヒンギャの人々は「常にこの国から出ていくことを考えています」とマウンソウナインさん。「でも、出ていくことも許されません。拘束され、移動も止められてしまうからです」

■「夢も希望も持てない」

ヒューマン・ライツ・ウオッチによると、昨年のクーデター以降、「無許可での移動」を理由に身柄を拘束されたロヒンギャは、子ども数百人を含め、約2000人に上る。

イスラム教徒が大多数を占めるマレーシアも、ロヒンギャ難民の主要な逃避先となっている。密航業者に命を預けていちかばちかで危険な旅に出る人も多い。今年5月には、ミャンマー南西部の海岸に14人の遺体が打ち上げられた。国連難民高等弁務官事務所(UNHCR)は、ロヒンギャ難民との見方を示している。

昨年、国軍が再び権力を握ったことで、ロヒンギャの人々が市民権を取得し、制限が緩和される希望はさらに薄れた。

国際医療援助団体「国境なき医師団(MSF)」に所属し、ミャンマーでの活動の代表を務めているマルヤン・ベサイェン氏は、キャンプで暮らしている人々にとっては家に帰ることすらかなわないだろうと話す。

「たとえ移動できたとしても、彼らがかつて住んでいた多くの村やコミュニティーは、もはや存在しません」

マウンソウナインさんは「この国では、私たちロヒンギャへの人種的憎悪が根強いのです」と述べ、「将来の夢も希望も持てません」と訴える。「私たちはただ、尊厳を持って人並みの生活を送りたいだけです」【翻訳編集AFPBBNews】

〔AFP=時事〕(2022/09/05-11:08)

Songs of praise-- Rohingya sing Myanmar anthem 5 years after exodus

Every morning in his refugee camp school, Mohammad Yusuf sings the national anthem of Myanmar, the country whose army forced his family to flee and is accused of killing thousands of his people.

Yusuf, now 15, is one of hundreds of thousands of mostly Muslim ethnic Rohingya who escaped into Bangladesh after the Myanmar military launched a brutal offensive five years ago on Thursday.

For nearly half a decade, he and the vast numbers of other refugee children in the network of squalid camps received little or no schooling, with Dhaka fearing that education would represent an acceptance that the Rohingya were not going home any time soon.

That hope seems more distant than ever since the military coup in Myanmar last year, and last month authorities finally allowed UNICEF to scale up its schools programme to cover 130,000 children, and eventually all of those in the camps.

But the host country still wants the refugees to go back: tuition is in Burmese and the schools follow the Myanmar curriculum, also singing the country's national anthem before classes start each day.

The Rohingya have long been seen as reviled foreigners by some in Myanmar, a largely Buddhist country whose government is being accused in the UN's top court of trying to wipe out the people, but Yusuf embraces the song, seeing it as a symbol of defiance and a future return.

Myanmar is my homeland, he told AFP. The country did no harm to us. Its powerful people did. My young sister died there. Our people were slaughtered.

Still it is my country and I will love it till the end, Yusuf said.

- 'Ticking bombs' -

The denial of education for years is a powerful symbol of Bangladesh's ambivalence towards the refugee presence, some of whom have been relocated to a remote, flood-prone and previously uninhabited island.

This curricula reminds them they belong to Myanmar where they will go back some day, deputy refugee commissioner Shamsud Douza told AFP.

But when that might happen remains unclear, and visiting UN human rights chief Michelle Bachelet said this month that conditions were not right for returns.

Repatriation could only happen when safe and sustainable conditions exist in Myanmar, she added.

She dismissed the suggestion that the Rohingya camps could become a new Gaza, but Dhaka is now increasingly aware of the risks that a large, long-term and deprived refugee population could present.

Around 50 percent of the almost one million people in the camps are under 18.

The government thought educating the Rohingya would give a signal to Myanmar that (Bangladesh) would eventually absorb the Muslim minority, said Mahfuzur Rahman, a former Bangladeshi general who was in office during the exodus.

Now Dhaka has realised it needs a longer-term plan, he said, not least because of the risk of having a generation of young men with no education in the camps.

Already security in the camps is a major problem due to the presence of criminal gangs smuggling amphetamines across the border. In the last five years there have been more than 100 murders.

Armed insurgent groups also operate. They have gunned down dozens of community leaders and are always on the lookout for bored young men.

Young people with no prospects -- they are not allowed to leave the camps -- also provide rich pickings for human traffickers who promise a boat ride leading to a better life elsewhere.

All the children could be ticking time bombs, Rahman told AFP. Growing up in a camp without education, hope and dreams; what monsters they may turn into, we don't know.

- Dreams of flying -

Fears remain over whether Bangladesh may change its mind and shut down the schooling project, as it did with a programme for private schools to teach more than 30,000 children in the camps earlier this year.

Some activists condemn the education programme for its insistence on following the Myanmar curriculum, rather than that of Bangladesh.

With few prospects of return, the Myanmar curriculum was of little use, said Mojib Ullah, a Rohingya diaspora leader now in Australia.

If we don't go back to our home, why do we need to study in Burmese? It will be sheer waste of time -- a kind of collective suicide. Already we lost five years. We need international curricula in English, he said.

Young Yusuf's ambitions also have an international dimension, and in his tarpaulin-roofed classroom he read a book on the Wright brothers.

He wants to become an aeronautical engineer or a pilot, and one day fly into Myanmar's commercial hub Yangon.

Someday I will fly around the globe, that's my only dream.

最新ニュース

-

米送還移民の引き渡し提案=エルサルバドル大統領がベネズエラに

-

世耕氏、還流再開決定を否定=22年の旧安倍派幹部会合

-

錦織は64位=男子世界テニスランク

-

「情熱戻った」マルシャン=パリ五輪4冠、次は世界水泳―競泳

-

ハマス、戦闘員3万人補充か=イスラエルの不発弾「再利用」も―報道

写真特集

-

ラリードライバー 篠塚建次郎

-

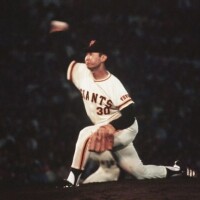

元祖“怪物” 巨人・江川卓投手

-

つば九郎 ヤクルトの球団マスコット

-

【野球】「サイ・ヤング賞右腕」トレバー・バウアー

-

【野球】イチローさん

-

【スノーボード男子】成田緑夢

-

【カーリング】藤沢五月

-

【高校通算140本塁打の強打者】佐々木麟太郎