ブラジル・水辺の貧民街、コロナ禍は多くの苦難のほんの一つ

【サントスAFP=時事】マングローブの生える水面から突き出た、細い材木を脚にして立つ家々。(写真はブラジル・サンパウロ州サントスにあるファベーラ<貧民街>、ディキダビラジルダの床板に立つ住民)

【サントスAFP=時事】マングローブの生える水面から突き出た、細い材木を脚にして立つ家々。(写真はブラジル・サンパウロ州サントスにあるファベーラ<貧民街>、ディキダビラジルダの床板に立つ住民)ブラジル南東部サンパウロ州にある南米最大の港湾都市、サントスを流れる川の河口には、ディキダビラジルダと呼ばれる同国最大級のファベーラ(貧民街)がある。ビーチ沿いの庭園で知られ、サンパウロの富裕層が週末を過ごすサントスのリゾート地区とは別世界だ。

ここの水辺は悪臭を放ち、ごみが散乱している。さびた金属とゆがんだ材木でできた家に暮らす住民らは、生き延びるために必死だ。

ディキダビラジルダのような地区とサントス市内のより裕福な地区との格差はこれまでも明白だったが、新型コロナウイルスの流行でさらに拡大した。

とはいえ、このブグレス川河口の貧民街では、コロナは数多くの悲惨な現状の一つにすぎない。

住民のエリエッテ・アウベスさんは「ここにはネズミ、ゴキブリ、デング熱、チクングニヤ熱、何でもあります」と語る。足元では同地区の住民2万6000人が投げ捨てたごみが、悪臭のする水の中に積もっている。

別の住民、ジュリアナ・ダシルバ・バルボサさん(35)は、2部屋だけの小さな掘っ立て小屋で6人の子どもを育てるシングルマザーだ。コロナ禍で子守の仕事を失い、今は給付金を受けてどうにかやっている。

バルボサさんはこれまでコロナには感染していないが、蚊が媒介する感染症のチクングニヤ熱にかかってしまった。ファベーラの住民は密集した不衛生な環境下で、伝染病にかかる危険にさらされている。【翻訳編集AFPBBNews】

〔AFP=時事〕(2021/07/12-11:02)

In Brazil favela on stilts, Covid one on a long list of woes

It's best to watch your step in Dique da Vila Gilda, a slum on stilts where the rickety walkways across the fetid water below the tin-roof shacks sometimes break beneath people's feet.

Deise Nascimento dos Santos, a 54-year-old resident of the neighborhood -- which holds the title of Brazil's biggest favela on stilts -- learned that lesson the hard way: with 23 stitches, the result of a nasty fall outside her house.

If you fall here, you stay here, she says.

Built on spindly wooden legs above the mangroves at the edge of the Bugres river, Dique da Vila Gilda is part of Santos, a city on Brazil's southeastern coast known for its beachfront gardens and the largest port in Latin America.

But the favela is a world apart from the resort district, a getaway for weekenders from wealthy Sao Paulo.

Here, the waterfront is putrid and littered with trash, houses are made of rusting metal and warped wood, and residents struggle to scrape out enough to survive.

The coronavirus pandemic -- which has claimed more than half a million lives in Brazil, second only to the United States -- has deepened the already stark inequalities dividing places like Dique da Vila Gilda from the more privileged side of town.

But Covid-19 is just one on a long list of woes in the slum, which was started -- like most favelas -- by rural migrants who arrived in the city looking for work and built impromptu houses in the only space they could find.

We've got rats, cockroaches, dengue fever, chikungunya -- everything, says Dos Santos's neighbor Eliette Alves.

She spends nearly 70 percent of her pension to pay the 500-reais ($100) rent on the shack she shares with her son, even though the floor is water-damaged and there is a gaping hole in her bedroom through which she can see the river below.

Her biggest fear is dying in a fire, like the one that razed several of her neighbors' houses in April.

It was horrible -- the sound of the wood crackling. All I could do was pray to God the flames wouldn't spread here, she says.

- 'Ticking bomb' -

The favela is a maze of makeshift walkways between the shacks, the gaps in the boards patched with scraps of wood and cardboard.

Below, trash cast off by the community's 26,000 inhabitants accumulates in the foul-smelling water.

I wouldn't even say we're getting by. Getting by would mean having food on our plates, jobs, education, decent housing, says Lucileia Siqueira de Santos, 39.

She rails against President Jair Bolsonaro, who she says is failing poor Brazilians.

She calls him a genocidal maniac, a line the far-right leader's critics use to condemn his anti-mask, anti-lockdown pandemic response.

But the frustration goes deeper than that. The pandemic turned an already desperate situation worse, costing many people in the favela their jobs, she says.

Everyone's talking about Covid, but we've got a lot of other problems, she told AFP.

Juliana da Silva Barbosa, 35, is one example.

A single mother raising her six children in a small two-room shack, she lost her job as a nanny because of the pandemic and is now surviving on handouts.

She resents the lack of schools and internet to educate her children.

The politicians only come here when they need our votes. This place is a ticking bomb, she says.

She has escaped Covid-19 so far, but contracted chikungunya, the mosquito-borne viral infection.

The crowded conditions and lack of sanitation in the favela leave residents highly exposed to communicable diseases.

Health services are non-existent in the slum.

Ambulances only come here when somebody dies, says Barbosa.

The social worker who used to come died of Covid, says Julio Silva, 39, who also lost his job in the pandemic.

At low tide, some residents venture out onto the water on homemade rafts to fish for their lunch.

Giovani Ferreira, 36, casts his net and pulls it back empty several times. But he doesn't give up. Earlier, he caught a tilapia and a mullet.

The tide always brings something, he says with a smile.

Lucileia is less optimistic.

We're at God's mercy here, she says.

最新ニュース

-

大谷、父親休暇リストから復帰=米大リーグ・ドジャース

-

富山市長に藤井裕久氏再選=共産系新人破る

-

松江市長に上定昭仁氏再選=共産新人ら破る

-

富山市長に藤井裕久氏再選=共産系新人破る

-

安楽が優勝=クライミングW杯

写真特集

-

ラリードライバー 篠塚建次郎

-

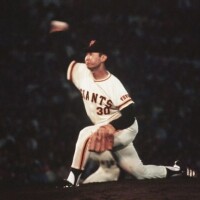

元祖“怪物” 巨人・江川卓投手

-

つば九郎 ヤクルトの球団マスコット

-

【野球】「サイ・ヤング賞右腕」トレバー・バウアー

-

【野球】イチローさん

-

【スノーボード男子】成田緑夢

-

【カーリング】藤沢五月

-

【高校通算140本塁打の強打者】佐々木麟太郎