国境超えて中東つなぐ弦楽器、オリエンタルリュート イラン

【テヘランAFP=時事】弦楽器のオリエンタルリュートが、イランで数十年ぶりに人気だ。分断された中東地域で、音楽家たちは国境を超えてつながり、アラブやトルコの伝統音楽に欠かせないこの楽器の魅力を再発見している。(写真はイラン・テヘランにあるファーテメ・ムサビさんのウード工房で、新作を試奏するイラン人ウード奏者)

【テヘランAFP=時事】弦楽器のオリエンタルリュートが、イランで数十年ぶりに人気だ。分断された中東地域で、音楽家たちは国境を超えてつながり、アラブやトルコの伝統音楽に欠かせないこの楽器の魅力を再発見している。(写真はイラン・テヘランにあるファーテメ・ムサビさんのウード工房で、新作を試奏するイラン人ウード奏者)アラビア語で「ウード」、ペルシャ語では通常「バルバット」と呼ばれる。ただし、それぞれの楽器は互いにやや異なるという主張もある。

首都テヘランでウードを教えるマジド・ヤーヤネジャドさん(35)。ウードを学ぶ人は「この15年ほどで大幅に増えました。有名講師だと生徒数は以前は10人程度でしたが、今では50人くらいでしょう」と言う。

テヘランに住む音楽家、ヌーシーン・パスダルさん(40)も同じように感じている。彼女は芸術の専門学校を卒業後、23年ほど前にこの楽器を教え始めた。「当時の生徒の大半はかなり高齢でしたが、今はもっと若くなっています」と言う。

「ウードについては、エジプトとイラクで演奏されていたことしか分からず、トルコのウードのことは何も分かっていませんでした。しかし今では、シリアやクウェート、ヨルダンでも演奏されていたことが分かっています」

■楽器を通じた友情

イランの若手ウード奏者たちはアラブやトルコの文化に寄せる関心が高く、「トルコ、アラブ、イランの音楽家同士、インターネット上で友人になっている」ことに、ヤーヤネジャドさんは気付いた。

イランとシリアは、ウードの製作とその演奏を国連教育科学文化機関(ユネスコ、UNESCO)の無形文化遺産に登録しようと活動している。

パスダルさんは、初めてウードに出会ったときのことを覚えている。音楽教師たちがウードを見せてくれたことがきっかけで、音楽家の集まるテヘラン中心部のバハレスタン広場まで楽器を探しに行った。

しかしわずか二つしか見つからず、どちらもエジプト製で、初心者には大きすぎるものだったという。

テヘランの小さな工房でウードを製作するファーテメ・ムサビさんによると、当時はウード製作者がほとんどおらず、高価な楽器だった。状況が変わったのは2000年代初頭。主にシリアとトルコから数千台のウードがイランに入ったことで、価格が下がった。

イランではイスラム教シーア派の聖職者によって聖典コーランと宗教法を学ぶことが優先されるが、当時は1997年から 2005年まで大統領を務めた改革派のモハマド・ハタミ師の下、自由化が進められていた。この時期、芸術シーンも時代の恩恵を受けることができた。

2016年にはテヘランの舞台で、イランのグループ「ガルドゥン」とレバノンのウード奏者が共演した。翌年はトルコの演奏者がこれに続いた。またペルシャ語の詩に曲を付け、イラン人音楽家を含めたオーケストラを率いて複数の演奏会を開いたチュニジア人奏者もいる。

ヤーヤネジャドさんは、音楽を介した交流が、何十年間も戦争や内戦に苦しんできた中東で、宗教や文化を超えた友情を育むことに希望を抱いている。「この地域の人々の和解に、この楽器が役立つことができるかもしれません」【翻訳編集AFPBBNews】

〔AFP=時事〕(2021/05/19-14:35)

Oriental lute makes comeback on Iran music scene

The Oriental lute is making a comeback in Iran after decades in the shadows as musicians reconnect with an instrument integral to Arab and Turkish musical tradition in a fragmented region.

Known as the oud in Arabic, it is commonly called the barbat in Persian, although some would argue the instruments differ slightly.

The number of (oud) students has increased considerably over the past 15 years or so; before a known teacher would have had a dozen students whereas today they'll be about 50, said Majid Yahyanejad, a 35-year-old oud teacher in Tehran.

Noushin Pasdar, a 40-year-old musician in the Iranian capital, made the same observation.

She started teaching the stringed instrument about 23 years ago after graduating from professional arts school, known as honarestan in Persian.

At the time, most of my students were old, really old. Now they're more on the young side, Pasdar said.

We only knew the oud as played in Egypt and Iraq. We knew nothing of the oud in Turkey. But today we know it's also played in Syria, Kuwait and Jordan.

- Internet friends -

Yahyanejad noticed young Iranian oud players were taking more interest in Arabic and Turkish culture... and Turkish, Arab and Iranian musicians are becoming friends on the internet.

The barbat has been around for centuries and it takes up a whole chapter of the Shahnameh (Book of Kings), written in the 10th century.

Iran and Syria are lobbying for the manufacture and playing of the oud to be added to UNESCO's intangible heritage list.

The barbat had fallen out of Iran's classical and traditional repertoires, with (other) stringed instruments such as the setar, tar, santur and kamancheh given preference.

But in the second half of the 20th century, a man named Mansour Nariman introduced oud instruction at the honarestan and published the first Persian-language manual on the instrument, Yahyanejad points out.

Nariman, who died in 2015, had been drawn to the warmth of its sound, at a time when the Arab oud did not even figure on Iran's musical periscope.

In the absence of any teachers back then, Nariman taught himself and wrote off letters to Egyptians he had heard playing the instrument on the radio.

He received a reply from one of the biggest names in Arab music, Mohamed Abdelwahab.

- Instrument to 'reconcile' -

Many years later, Mohammad Firouzi, a student of Nariman, recorded several pieces of music with the undisputed maestro of Persian song, Mohammad-Reza Shajarian, who died in October.

Among them were masterpieces such as Aseman-e Eshgh in 1991, Aram-e Jan, 1998, and Ghoghaye Eshghbazan, in 2007.

Pasdar remembers the first time music teachers showed her an oud, triggering a hunt for the instrument in central Tehran's Baharestan Square, a paradise for musicians.

She said she found only two, both made in Egypt, and too bulky for a budding musician.

Fatemeh Moussavi, who crafts ouds in a small Tehran studio, says very few artisans manufactured the instruments and they were pricey back in the day.

Things didn't change much until the early 2000s, when thousands of ouds landed in Iran, mostly from Syria and Turkey, bringing down prices.

It was a time of liberalisation under the reformist Mohammad Khatami who served as president between 1997 and 2005.

The arts scene benefitted from this period in the Islamic republic, where the Shiite clergy prioritises study of the Koran holy book and religious jurisprudence.

For Hamid Khansari, who has written an introduction to the oud, the bow-shaped instrument is a blessing that expands the possibilities of creation.

Lebanon's Charbel Rouhana played the instrument on stage in Tehran with Iranian group Gardoun in 2016, followed the next year by Yurdal Tokcan from Turkey.

Tunisian Dhafer Youssef has woven Persian poems into his repertoire and given several concerts with Iranian musicians figuring in his international orchestra.

In a Middle East tormented for decades by war and conflict, Yahyanejad harbours hope that musical interaction will forge bonds of friendship across religions, ethnicities and cultures.

This instrument could finally help reconcile peoples of the region.

最新ニュース

-

復活祭停戦が終了=ロシア

-

大谷、父親休暇リストから復帰=米大リーグ・ドジャース

-

富山市長に藤井裕久氏再選=共産系新人破る

-

松江市長に上定昭仁氏再選=共産新人ら破る

-

富山市長に藤井裕久氏再選=共産系新人破る

写真特集

-

ラリードライバー 篠塚建次郎

-

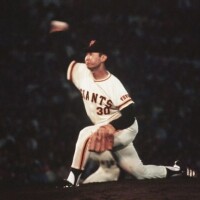

元祖“怪物” 巨人・江川卓投手

-

つば九郎 ヤクルトの球団マスコット

-

【野球】「サイ・ヤング賞右腕」トレバー・バウアー

-

【野球】イチローさん

-

【スノーボード男子】成田緑夢

-

【カーリング】藤沢五月

-

【高校通算140本塁打の強打者】佐々木麟太郎