アウシュビッツ解放75年、生存者が語る「消えない恐怖」

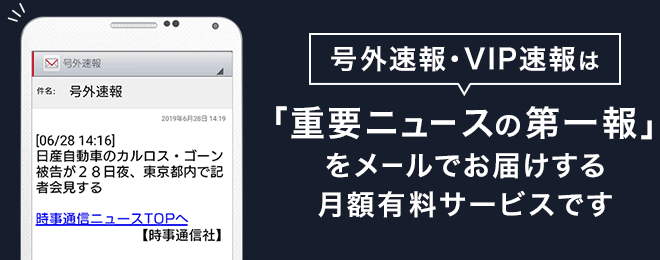

【エルサレムAFP=時事】ナチス・ドイツがポーランドに設置したアウシュビッツ・ビルケナウ強制収容所の解放から27日で75年を迎える。AFPでは、死の収容所を生き延びたユダヤ人らにインタビューを行った。(写真は腕に入れられたアウシュビッツの囚人番号を見せるホロコーストの生存者シュムル・イツェクさん)

【エルサレムAFP=時事】ナチス・ドイツがポーランドに設置したアウシュビッツ・ビルケナウ強制収容所の解放から27日で75年を迎える。AFPでは、死の収容所を生き延びたユダヤ人らにインタビューを行った。(写真は腕に入れられたアウシュビッツの囚人番号を見せるホロコーストの生存者シュムル・イツェクさん)アウシュビッツでは何百万ものユダヤ人が殺された。残った生存者らは高齢となり、左手に刻まれた囚人番号の入れ墨は薄れた。だが、当時の恐怖によって心と体に刻まれた傷は今も消えることなく残っている。

■シュムル・イツェクさん

1927年9月20日ポーランド生まれ/アウシュビッツ囚人番号117 568

アウシュビッツで亡くなった両親と姉妹の写真を見るシュムル・イツェクさん(92)の体は震え、目は涙で曇っている。

1942年初め、悪名高いナチスの秘密警察ゲシュタポからの通知を受け、イツェクさんの2人の姉妹は出かけて行った。家族を守るため、ゲシュタポの元を訪れなければいけなかったのだ。

「2人は出かけて行って、二度と戻ってこなかった。2人がどうなったのかは分からない」。交通事故に遭い、話すことが困難になった夫に代わり、妻のソニアさんが答えた。

イツェクさんは長年、アウシュビッツにいたことを妻には秘密にしていた。

イツェクさんら夫婦はベルギーで長年暮らした後、イスラエルへと移り住んだ。今は、エルサレムのアパートで暮らしている。居間の壁にはイツェクさんの家族の古い写真が飾られている。

姉妹2人がいなくなってから1か月後、ドイツ人らが家を訪れ、今度はイツェクさんの両親、2人の兄弟、イツェクさんを連れ出した。

「列車を降りてアウシュビッツに着くと、少年のように父親の手を握った」

だが、イツェクさんはナチスによって父親から引き離された。「父親と一緒にいたかったので泣いた。ドイツ人から『おまえはあっちだ』と言われた」と当時を振り返った。

父親の姿を見たのはこれが最後だった。父親はガス室に送られた。両親は死んだが、イツェクさんと兄弟2人は生き残った。イツェクさんは2年半、アウシュビッツに収容されていた。

他の生存者とは異なり、イツェクさんが戦後にアウシュビッツを再び訪れることはなかった。アウシュビッツに関する本を読むことも避けていた。

イツェクさんは長年、長袖の服を着て囚人番号の入れ墨を隠していた。しかし、最近になって、入れ墨を隠さなくなったという。

「これまで見せたくなかったけど、今ではタクシーに乗ったら最初にこうしている」と、ソニアさんはイツェクさんの腕を見せながら言った。

「夫は恥ずかしく思っていたようだったので(中略)、私はこう言った。『あなたは収容所に行った。あなたは幸せでいなくては。生き残ったのだから』」

■メナヘム・ハバーマンさん

1927年チェコスロバキア生まれ/アウシュビッツ囚人番号10 011

メナヘム・ハバーマンさんはイツェクさん同様、家族と引き離され、アウシュビッツに収容された。まだ10代だった。

8人のきょうだいで生き残ったのはハバーマンさんだけだった。収容所の外にある用水路に連れて行かれ、シャベルを渡された時のことを詳しく話してくれた。

「用水路の両側を忙しく行き来し、水に灰を流さなければいけなかった。私は自分が何をやっているのか分からなかった。作業後、ここでの収容経験が長い人に聞いてみた。『私は何をしていたのですか』と」

「その人は『あなたの家族は全員、ここに到着して4時間後には灰になって水に流されたんだ』と答えた」「私がどこにいるか理解したのはその時だった」とハバーマンさんはAFPに語った。

「私は自分自身に、ここで死にたくない、自分の灰がこの用水路から川に流されるのは嫌だと言い聞かせた」「(ユダヤ人の言語)イディッシュ語で、こう言っていた男性がいた。『働く力がない者は、煙突行きだ』」

「私はその言葉を胸に刻み、繰り返し考えた。ここで死にたくないと」

「毎日、特に夜になるとそのことを考えた」とハバーマンさんは言う。「それは私の中に深く染み付いている。75年たった今も、その言葉と共に生きている。忘れたことはない…忘れられない」

■マルカ・ザケンさん

1928年ギリシャ生まれ/アウシュビッツ囚人番号79 679

テルアビブ郊外の小さなアパートで、マルカ・ザケンさん(91)は、人形に囲まれて暮らしている。まだもともとの箱に入っている人形もある。

ザケンさんはAFPの記者が到着すると、「ショーン、彼はドイツ人ではないから心配しないで。あなたを連れて行かないから」と、そのうちの1体に話し掛けた。

高齢のためザケンさんの記憶は混乱している部分もあり、話も不明確なところがあるが、アウシュビッツのトラウマは鮮明に記憶に焼き付いている。

「幼いころ、母は私にたくさんの人形を買ってくれた」と、ギリシャで両親と6人のきょうだいと暮らしていた子どものころを振り返る。

「でも、母はナチスに焼かれてしまった。人形たちと一緒にいると母を思い出す。まるで、まだ子どもで家にいるような気持ち。そのことをいつも考えている」と語った。ザケンさんは、家で介護人とテレビドラマを見ながら午後を過ごしている。

アウシュビッツでは、いつも殴られたとも話した。「私たちは裸で、彼らは私たちを殴った。(中略)どれだけ苦しんだか決して忘れない、決して忘れない、決して」「なんてこと! なぜ、私が生き延びたのかも分からない」

ガス室の恐怖におびえていたこと以外では、死の収容所で誰もが経験した飢えについても覚えていた。極度の飢えにより、囚人らは歩く骸骨のようになっていたとザケンさんは話す。

■サウル・オレンさん

1929年ポーランド生まれ/アウシュビッツ囚人番号125 421

同じくアウシュビッツを生き延びたサウル・オレンさん(90)も、「残忍な」飢えについて語った。オレンさんによると、囚人らに与えられたのは水っぽいスープだったという。

「スープだけで1日過ごすこともあった。または小さなジャガイモかパンのかけらを与えられることもあった」

「後々まで取っておきたかったので、パンを全部食べようとは思わなかった」

オレンさんの母親はアウシュビッツで殺された。母親の写真は残っていないが、絵を描くことで、母の姿を残そうとしている。

強制収容所を出た後も、飢えはオレンさんに付きまとった。

旧ソ連軍が進攻してくると、ナチスは「死の行進」を敢行し、囚人らを厳しい寒さの中で強制収容所からドイツとオーストリアに向けて歩かせた。

「私たちは12日間、ほとんど食べる物もなく歩いた。(中略)森で休んだ時、死んだ馬を見つけた。全員が馬の死骸に群がり、食べた」とオレンさんは回想録に書いている。

■シュムエル・ブルメンフェルドさん

1925年ポーランド生まれ/アウシュビッツ囚人番号108 006

シュムエル・ブルメンフェルドさんも「死の行進」の生存者だ。ブルメンフェルドさんは、ホロコースト(ユダヤ人大量虐殺)で主要な役割を果たしたアドルフ・アイヒマンの看守をしたことがある。

イスラエルに連行されたアイヒマンは、エルサレムで裁判を受け、1962年に絞首刑となった。

ブルメンフェルドさんはアイヒマンに向かってアウシュビッツの入れ墨を見せながら、「おまえの部下は命令を完遂できなかったぞ。私は2年間あそこで過ごしたが、まだ生きている」と言ったという。

ブルメンフェルドさんは近年、ポーランドを繰り返し訪れ、家族が殺されたそれぞれの場所から土を持ち帰っている。土は、黄ばんだ小さな袋に入っていて、それを自分の墓に一緒に入れるよう自身の子どもたちに頼んであるという。

ブルメンフェルドさんは高齢だが、今もイスラエルの若者らとポーランドを訪れている。

■バットシェバ・ダガンさん

1925年ポーランド生まれ/アウシュビッツ囚人番号45 554

上品な雰囲気を漂わせたバットシェバ・ダガンさん(94)は、今でも活動的だ。人生を未来の世代の教育にささげてきた。これまでに本を6冊執筆しているが、うち5冊は子ども向けの書籍だ。

強制収容所を出たダガンさんは、「生き延びて(人々に)伝える」ことを決心したのだという。

ダガンさんはアウシュビッツの近くにあるビルケナウ収容所の倉庫で働いていた。そこには、靴など囚人の持ち物が積み重ねられていた。「私は20か月そこで過ごした。600日間ずっと」

ダガンさんの仕事は、収容所に到着したユダヤ人の旅行かばんを燃やし続けることだった。

「いつも死におびえながら、何時間も働いた。これが最後かもしれないと常に思いながら暮らしていた」

子どもたちに教えることで、自身の経験を前向きなものにしたいとダガンさんは考えていると話し、「ホロコーストの恐怖だけを物語るのではなく、お互いが助け合っていたこと、パンのかけらを分かち合えたこと、友情など素晴らしいことも話すようにしている。(中略)私たちは人間性を失わなかった」と続けた。

「私は生きている。(中略)苦しみは克服した!」【翻訳編集AFPBBNews】

〔AFP=時事〕(2020/01/27-12:58)

The last survivors-- growing old with memories of Auschwitz

As he looks at pictures of his parents and sisters who perished in Auschwitz, Szmul Icek begins to tremble, tears clouding his eyes.

It may have been 75 years ago, but for this survivor of the Holocaust the memories of life and death in the Nazi extermination camp remain painfully fresh.

More than a million Jews were killed at Auschwitz, in then occupied Poland. The last survivors, now all elderly, still live with the physical and mental scars of the horrors of that time.

Since their liberation three quarters of a century ago, their skin has wrinkled with the march of time and the numbers tattooed on their left arms have faded.

Much in the same way that the collective memory of the Holocaust is blurring.

These survivors are the last witnesses to traumatic events which now in the 21st century are often called into question by anti-Semitic revisionists.

So as Israel prepares this month to mark the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the camp at a ceremony to be attended by a host of world leaders, AFP reporters met with about 10 survivors to hear their testimonies.

Some have learnt their stories by heart, reciting every detail -- without tears.

Others no longer have the strength to speak, some have had their memories ravaged by Alzheimer's. While others are still consumed by the shame of being one of Adolf Hitler's victims.

Born in Poland, Icek, 92, struggles to talk following a car accident, and leaves it to his wife to recount the tragedy which befell his family.

In early 1942, his two sisters responded to a notice from the Gestapo that children should present themselves to the notorious secret police in order to protect their family.

They left, but they were never seen again, never. We don't know what happened to them, said Sonia on behalf of her husband, who tensed up as she began to talk.

For many years, Icek, number 117 568, kept his imprisonment at Auschwitz secret from his wife.

After living together in Belgium for years, the couple now inhabits an apartment in Jerusalem where old family portraits hang in their living room.

One shows his father with a full beard, wearing a round hat, while his mother's hair is cropped short in the style popular in that era.

A month after his sisters disappeared, the Germans came for the rest of his family. His parents, two brothers and him.

When he arrived at Auschwitz, on getting off the train, he held onto his father's hand like a little boy, Sonia said of her husband's deportation.

But Icek was separated from his dad by a Nazi. He cried, he wanted to be with his father. But the German said: 'no, you (go) over there'.

That was the last time he saw his father, who was sent to the gas chambers. Both his parents died, although his brothers like him managed to survive.

Hearing his wife talk about Auschwitz where he spent two and a half years, Icek, dressed in a blue polo neck and a skullcap, became briefly animated.

It can't be, it can't be, no, he said, clasping his hands around his neck to mime the killings at the camp.

- Burying the ashes -

Like Icek, Menahem Haberman, born in the then Czechoslovakia in 1927, was a teenager when he arrived at Auschwitz and was separated from his family.

Their paths never crossed at the extermination camp, nor in Jerusalem where Haberman now lives in a retirement home.

His memory still sharp, he recounted how he was taken outside of the camp to the edge of some water and given a shovel.

There was a canal and I had to run to each side and pour ashes into the water. I didn't know what I was doing. When I came back, I asked a camp veteran: 'What have I done?'

Haberman told the man he had only arrived at Auschwitz the previous day.

He told me: 'All your family were ashes in that canal four hours after their arrival.'

It was then that I understood where I was, Haberman told AFP.

His bitter encounter with death at the camp was to drive his overwhelming determination to survive.

I told myself, I don't want to die here, I don't want my ashes to sink and flow in this canal towards the river, said Haberman.

There was a guy there who said in Yiddish: 'Those who don't have the strength to work, will end up in the chimney.'

I kept that phrase in mind and repeated: I do not want to die here.

The experiences of the last remaining survivors, who were children when they were sent to the death camps, remain seared into their minds.

Every day I think about it, especially at night, said Haberman.

It's deeply engrained in me. Seventy-five years later, we still live with that, we don't forget... we cannot forget, said Haberman.

We are survivors, we are not escapees. The camps are imprinted in our skin.

Six million Jews were killed by Nazi Germany. And of more than 1.3 million people imprisoned at Auschwitz, some 1.1 million died and Haberman remains baffled that he managed to survive.

I really knew people who were better men than me. Why did they die and why am I still alive?

- Stalked by hunger -

In the suburbs of Tel Aviv, 91-year-old Malka Zaken sits in her small apartment surrounded by dolls, some of which are still in their original boxes.

Don't worry Sean, he's not German, he won't take me, Zaken reassured one of them, as AFP arrived to talk to her.

While age has muddled some of her memories and her speech is confused, the traumas of Auschwitz remain vivid.

When I was little, my mother bought me lots of dolls, said Zaken, recalling her childhood in Greece with her parents and six siblings.

But she was burned by the Nazis. When I'm with the dolls, I remember her, it's like when I was a child at home, I think about it all the time, she said.

Zaken spends her afternoons watching soap operas, at home with a carer.

She remembers friends killed by the Nazis, as well as those who survived the war but have since died.

In Auschwitz, she recalled being beaten all the time, we were naked and they beat us... I never forget, never, I never forget how much I've suffered.

What hell! I don't even know how I made it to survive.

Occasionally looking dazed, the number 76 979 marked on her wrinkled skin, Zaken said the memories haunted her long after she was freed.

After the liberation, I couldn't sleep, I lay awake at night crying, I was scared, and I was cared for for a long time.

As well as fearing the gas chamber, Zaken also remembers the starvation which stalked the death camp and reduced prisoners to walking skeletons.

Fellow survivor Saul Oren, 90, also recalled the unimaginable hunger with prisoners given watery soup.

And the soup was for the whole day. Or they gave us a small potato, or they gave us a small piece of bread, he said.

We didn't dare eat the whole bread because we wanted to save it for later, perhaps we couldn't stand the hunger, he said.

Oren's mother was killed at Auschwitz and he has no photo of her, but tries to include her image in the paintings he does at home.

Even after leaving the extermination camp, hunger followed him.

He was forced onto the Death March when, as the Soviets advanced, the Nazis made prisoners from extermination camps walk in deep winter towards Germany and Austria.

We marched for 12 days, practically without eating... we stopped in a forest, we found a dead horse, everyone threw themselves on the horse. Each person took a bite, Oren said.

Another survivor, Danny Chanoch, marched for weeks in the snow, scratching at the soil in the hope of unearthing some frozen grass.

He is still affected by seeing survivors eating the bodies of prisoners killed by the Germans.

They couldn't stand the hunger so they took the human flesh, cooked, ate (it).

And we know that a red line is not to eat human flesh and not to take the bread from your comrade, said Chanoch, originally from Lithuania.

- Guarding Eichmann -

After being taken to the Mauthausen and Gunskirchen camps, Chanoch was eventually freed and made his way to Italy as a penniless 12-year-old.

In the city of Bologna he was reunited with his brother, Uri, and a photo of the two boys taken by an Italian man hangs in his home.

Chanoch, who lives in a village between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, was philosophical about his experience in the death camp: Sometimes I say to myself, 'how could I live without Auschwitz?'

It led me to the right way, to not skip anything, and do what you like to do, he said.

Chanoch and his brother travelled illegally from Italy to Palestine, then under British mandate, while other Holocaust survivors later arrived in the land which had become Israel.

The new state swiftly passed a law setting out the death penalty for crimes against the Jewish people, crimes against humanity and war crimes.

The legislation was used to execute Adolf Eichmann, one of the masterminds of the Nazis' so-called Final Solution plan of genocide against European Jews. He was captured in the Argentinian capital Buenos Aires 15 years after the war and smuggled to Israel, and tried.

For Shmuel Blumenfeld, a 94-year-old Auschwitz survivor, tattooed with number 108 006, the Eichmann affair was a historic turnaround.

Blumenfeld served as one of Eichmann's prison guards and spoke to the Nazi, telling him who had ultimately won.

One day I brought him food, I lifted my sleeve so that he saw my tattooed number. He saw it but acted as if nothing was amiss, said Blumenfeld, who offered Eichmann another helping.

Then, I clearly showed my number from Auschwitz and I told him: 'Your men didn't finish their mission, I spent two years there and I'm still alive', Blumenfeld said in German, before translating the conversation into Hebrew.

Once Eichmann shouted to complain that he couldn't sleep, because there was too much noise. And I said to him: 'We are not in the office of Adolf Eichmann in Budapest, you are in the office of Shmuel Blumenfeld'.

At his home, Blumenfeld keeps a fabric bag of earth collected from the places where all his family members were killed.

My mother told me 'never forget that you are Jewish' and I obeyed her, said Blumenfeld, who spent his career in the Israeli prison service.

- 'I overcame' -

Despite his age, Blumenfeld continues to travel to Poland with groups of young Israelis.

At almost 95, the elegant Batcheva Dagan also remains energetic and determined to use her experiences to educate future generations.

After making it out of a camp alive, she said she had one thing in mind: Survive to tell (people).

She worked in the heart of Birkenau camp, which neighboured Auschwitz, at a depot where shoes and other prisoners' belongings piled up.

I spent 20 months there, 600 days and nights, said Dagan, who had to burn the luggage of Jews who arrived at the camp.

Work out the hours and the seconds, thinking that each second you're scared of dying. You have an idea of what that means, living each moment with the threat that that moment is your last.

I try to make something positive out of my experience for children, educational.

I don't only recount the horror of the Holocaust, but also wonderful things like helping each other, the capacity to share a piece of bread, the friendship... We remained human beings.

The survivors' sense of victory comes through their poems, memories, but above all through living their daily lives and seeing future generations grow up.

I'm alive... I suffered, but I overcame! said Dagan.

Icek, who for years hid his Auschwitz tattoo under long shirts, has recently started to uncover it.

You didn't want to show it. Now the first thing that you do when you get into a taxi, you do this, his wife Sonia said, showing his forearm.

It's like he was ashamed... I told him: 'You have been to the camp, you must be happy, you came back,' said Sonia, who had to hide during the war in Belgium to avoid being sent to a death camp.

Sitting next to his wife, Icek said just three words before starting to cry: I have won.

But Sonia disagreed, saying he didn't win anything and lost his family whose pictures hang next to those of their grandchildren.

We have not won, but we have taught our grandchildren in a way that they understand what happened.

最新ニュース

-

最低賃金上げ、来春対応策=石破首相が意向―政権初の政労使会議

-

靖国参拝誤報「極めて遺憾」=共同通信に説明要求―林官房長官

-

一口サイズのクランチチョコ=ブルボン

-

元県議丸山被告に懲役20年求刑=無罪主張、妻殺害事件―長野地裁

-

防衛増税「必要なし」=税制改正協議難航も―国民・玉木氏

写真特集

-

【野球】慶応大の4番打者・清原正吾

-

【競馬】女性騎手・藤田菜七子

-

日本人メダリスト〔パリパラリンピック〕

-

【近代五種】佐藤大宗〔パリ五輪〕

-

【アーティスティックスイミング】日本代表〔パリ五輪〕

-

【ゴルフ】山下美夢有〔パリ五輪〕

-

閉会式〔パリ五輪〕

-

レスリング〔パリ五輪〕